Comedy by Black Comedians in the Turbulent 1960's

Intro to Archive

This archive contains five short biographies of noteworthy black comedians who were active during the 1960's. All of these comedians contributed somehow to the Civil Rights Movement, often in surprisingly unique ways.

This particular archive's purpose is to compare the social and political opinions of these five men, who all worked at some point in their lives as comedians, were born in lower income families, and identified as black males. Their similar occupation, background, and nationality would likely persuade anyone into assuming that their respective affiliations and beliefs during the Civil Rights Movement would unite them under one single banner, but their doctrines often could never be more different.

The images and documents archived are all from the Digital Public Library of America, whose dates of publications range from the late 1950's to the early 1970's, during the height of the Civil Right's Movement.

This archive may contribute more to the discussion of diversity than many other archives, because while others analyze the diversity of beliefs, culture, and political affiliations between different races, genders, or communities, this archive focuses on the diversity within a race of people, proving how an individual's race or background does not necessarily limit them to subscribing to a single ideological archetype. The practice of pigeonholing people based on the color of their skin, sexual orientation, or faith system is extremely present in today's society (common examples include labeling all black people as democrats, all white people as republicans, or LGBT members as liberals, etc) I hope that my archive will serve as a reminder to all people that diversity within race can be just as polarizing and varied as diversity between races.

Dick Gregory Bio

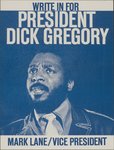

Of all the comedians in my archive, Dick Gregory certainly participated the most in the Civil Rights Movement. Prior to his big break in comedy, he performed mostly in segregated black comedy clubs, making a name for himself with his "no-holds-barred" sense of humor. In 1961, Gregory essentially became a household name overnight when he was hired as a replacement act at the Playboy Mansion, and asked to perform in front of a group of visiting white businessmen from the South, which was wildly infamous at the time for its segregation. After a riveting performance, Gregory's stay was extended by weeks, and even made an appearance that same year at the coveted Jack Paar's Tonight Show. Gregory would go on to perform in front of predominately white entertainers and audiences for most of his career, showing off his trademark comedic sociopolitical commentary style of humor. The celebrated comedian would also become known as one of the leading figures of the Civil Rights Movement, participating in the March on Washington, as well as various hunger strikes, sit-ins, and even a missing person's case (investigating the sudden disappearance of three civil rights workers) Gregory even dabbled in politics, unsuccessfully running for the positions of Mayor of Chicago and the President of the United States of America. To many people, Dick Gregory represented the type of activist who was wholeheartedly dedicated to both his craft and the advancement of equality (Lorts).

Dick Gregory Image Archive

[Images Complement of the Digital Public Library of America]

Sammy Davis Image Archive

[Images Complement of the Digital Public Library of America]Sammy Davis Bio

Another important performer of the Civil Rights Era was Sammy Davis Jr. Although he is more commonly known for performing alongside the legendary Frank Sinatra, Davis contributed more than his fair share to the world of comedy and civil rights. Davis's style of comedy was defined by his knack for imitations, humorous dancing, and incorporation of instruments in his act. Shows starring the comedian would often start out following one medium of entertainment, such as stand-up, and then repeatedly evolve into something completely different, showcasing his tremendous talent. Despite his warm reception on stage, Davis often faced prejudice at the areas he performed, often forced to enter and exist through the kitchen, not allowed suites at hotels, and forced to eat at different restaurants. It was likely because of his experiences of discrimination that he invested a large sum of his earnings into the Civil Rights Movement. Despite his involvement, Davis found it difficult to garner support from his fellow black Americans, as his personal life and beliefs differed greatly from that of the average black man during the 1960s. Davis was Jewish, had a history of substance abuse, married a white woman, and most infamously, was a vocal admirer of republican presidential candidate Richard Nixon during the race of 1968, while most black voters preferred the democrat nominee, Hubert Humphrey. Sammy Davis was a controversial figure during his time, but was an ally to the Civil Rights Movement nonetheless, who exemplified the uniqueness and individuality of many of its proponents at the time (Lorts).

Tim Moore, Spencer Williams, and Alvin Childress Bio

Amos 'n' Andy was the name of a sitcom that aired from 1951 to 1953, starring three prominent black comedians, Tim Moore, Spencer Williams, and Alvin Childress. The series was a remake of a radio show originating from the 1930's, which at the time, was written and voiced by an all white group of writers and actors. When the producers began casting for a live action adaptation, Moore, Williams, and Childress were chosen to star as the three main roles. At the time, all of these actors were popular among black audiences, as they had each starred, written for, or even directed, noteworthy race films (films starring a cast exclusively composed of one race, in this instance, black actors and actresses) Despite promising leads, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) almost immediately began protesting the show, citing its many negative connotations and stereotypes, such as the moronic character's lack of proper grammar, general crudeness, and perpetuating the idea of the working class black man as lazy and underachieving. Despite its respectably high ratings at the time, the show was pulled from TV less than two years after it was aired, ultimately ending the careers of the seasoned actors affiliated with it. Some of the leads even held prejudiced feelings against the NAACP for taking away their jobs, occasionally even refuting its claims, such as when Childress said, "I don't feel [Amos 'n' Andy] harmed the Negro at all. Actually the series had many episodes which showed the Negro with professions and businesses like attorneys, store owners and so on which they never had in TV or movies before." (Los Angeles Times) Nonetheless, the Amos 'n' Andy show is a prime example of how the activism of the Civil Rights Movement may have worked against the careers of some black Americans, causing animosity between the organization and those its very foundation was dedicated to protect (Lorts).

Spencer Williams & Alvin Childress

[Images Complement of the Digital Public Library of America]

Stepin Fetchit Bio

Lincoln Perry, more commonly known by his stage name, Stepin Fetchit, is honored as the first black actor to receive an official screen credit in a film, as well as one of the first black actor millionaires. However, his legacy during the Civil Rights Movement was largely viewed as an outdated relic from an earlier time, and so he was therefore ultimately tossed aside by members of the black community. Perry invented his character Fetchit in order to gain the attention of silent film producers, portraying himself both as a thoughtless, lazy, and useless character, whose primary role was to be a comic relief. Although he was largely successful in the eyes of white audiences (who gave him the honorary title of "Laziest Man in America"), Perry was an unspoken enemy to many black activists, who put tremendous pressure on Hollywood during Perry's career to get rid of any negative portrayals of black men and women in film or television. Although he never actively fought against the Civil Rights Movement, many of his quotes, both in front of and behind the camera, seemed to inflame relationships between the actor and the protesters. For example, after a mob contributed to the lynching/murder of an accused black man near Poplarville, Mississippi, Perry garnered a fair amount of negative attention for blaming that particular event and many others not on racist lynch mobs, but on communist spies trying to cause social turmoil in the country. To many black Americans, Lincoln Perry was a constant reminder of the perpetuation of a harmful and poisonous stereotype of his people, and instead of using his platform to fight against the prejudice, unwittingly contributed even more to it (Lorts)

.

Stepin Fetchit Archive

[Images Complement of the Digital Public Library of America]

Conclusion

In conclusion, I feel that my archive showcases the duality of black comedians during the Civil Rights Movement. While many actors were strong supporters of the movement, a few turned away from the movement and inflamed race relations by either encouraging stereotypes in their art, such as the case of Stepin Fetchit, or denouncing the institutions that encouraged positive race relations, such as Alvin Childress. Others, like Dick Gregory or Sammy Davis Jr., might have had differing opinions in certain aspects, but were still united under the belief that all men were creted equal, regardless of the color of their skin.

Works Cited

Works Cited

BURT A. FOLKART | Times Staff Writer. “Alvin Childress, 78, of 'Amos 'n' Andy' Series on TV, Dies.” Los Angeles Times, Los Angeles Times, 22 Apr. 1986, articles.latimes.com/1986-04-22/local/me-1453_1_amos-n-andy.

Lorts, Justin T. Black Laughter / Black Protest: Civil Rights, Respectability, and the Cultural Politics of African American Comedy, 1934-1968. Graduate School-New Brunswick, 2008.

―This archival exhibit was created by Kieran Croucher in Literature and Digital Diversity, fall 2017.