About/How to Navigate

I encourage you, the reader, to explore any and all of the outside sources in order to obtain some perspective, and examine all the great works that are featured in this archive. Simply scroll through and interact with this archive by clicking on the links in red or navigating through the image gallery slider by pressing the arrows.

I hope you enjoy reading this archive as much as I enjoyed making it!

Introduction

Except, what’s missing from this picture?

Susan B. Anthony, Eleanor Roosevelt, and Gloria Steinem are all white.

G. E. Perine & Co. (N.Y.)

Array

G. E. Perine & Co. (N.Y.)

Roosevelt, Franklin D. (Franklin Delano), 1882-1945

Roosevelt, Franklin D. (Franklin Delano), 1882-1945

And that is what this archive attempts to rectify and highlight: include the women of color who made feminism what it is today. Additionally, this archive strives to amplify the voices and stories of the women who were silenced, excluded, or flat out erased during the birth of feminism.

This archive consists of five biographies of exceptional black women who were imperative to the concept of feminism, as we know it today. All of these women contributed to the creation of the notion of feminism, often in remarkable ways.

I hope this archive will contribute to the discussion of inclusivity and diversity in the sense that it hones in on the diversity of race within a specific gender, both of which were—and still continue to be—oppressed. Additionally, my hope is that this archive will serve as a testament to how powerful and influential these women of color were to, not only feminism, but to women and equality as well.

Providing Perspective and “White Feminism”

Mariana Ortega’s essay “Being Loving, Knowingly Ignorant: White Feminism and Women of Color,” breaks down this ideal nicely. Ortega starts the essay with an anecdote about Audre Lorde speaking at a panel about feminism in 1979; she writes how Lorde is one of the only African-American women who have been invited, and while this conference that Lorde is speaking at is centered around feminism, Lorde wonders “how the audience deals with the fact that women of color are cleaning their houses, and taking care of their children.”

A powerful excerpt from Ortega’s essay touches on the fact that feminists are only all inclusive when it matter, or when the spotlight is shined on them. Ortega writes, “Why is it then that the list of respected women of color is still so short? Why is it that feminists still scramble to fill out the spot for the respected, well-known woman-of-color speaker that will bring in a crowd?” (15)

“Why is it then that the list of respected women of color is still so short? Why is it that feminists still scramble to fill out the spot for the respected, well-known woman-of-color speaker that will bring in a crowd?”

I’d like to end this introduction by encouraging you to read not only Ortega’s essay, but also the works that all of the women mentioned here published, in order to get a better understanding of how we can all truly be feminists that all fight for one another, instead of simply fighting one another. Additionally, I’d like to share a particularly moving quote from Audre Lorde that sums up the true ideal of feminism, and what it was established for.

“I am not free while any woman is unfree, even when her shackles are very different from my own.” ~ Audre Lorde

Video: “Why Feminism Fails Black Women”

Angela Davis’ Biography

“I am no longer accepting the things I cannot change. I am changing the things I cannot accept.” ~ Angela Y. Davis

bell hooks’ Image Gallery

bell hooks’ Biography

“I will not have my life narrowed down. I will not bow down to somebody else’s whim or to someone else’s ignorance.” ~ bell hooks

Alice Walker’s Biography

“The animals of the world exist for their own reasons. They were not made for humans any more than black people were made for white, or women created for men.” ~ Alice Walker

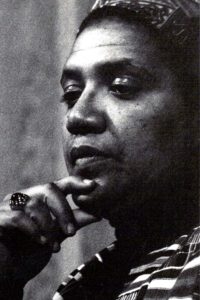

Audre Lorde’s Image Gallery

Audre Lorde’s Biography

“It is not our differences that divide us. It is our inability to recognize, accept, and celebrate those differences.”

― Audre Lorde, Our Dead Behind Us: Poems

Tarana Burke’s Biography

“‘Me Too’ is about letting – using the power of empathy to stomp out shame.” ~ Tarana Burke

Reflection/Takeways

I wish that was the end, and I was able to carry on with my intended project.

But it wasn’t.

As I expected, but deep down in my heart hoped against, the permissions for image use was pretty strict, I had to get explicit permission to use such images, and with Essence being such a big magazine, I knew the chances of them not only seeing my email, but actually responding to it and giving me permission, were next to none.

So it was back to the drawing board.

I knew I wanted to do something that focused on women of color and their stories being silenced, but I just didn’t know what.

But somehow—maybe by some stroke of luck, or the universe cutting me some slack—I got inspired.

I was going to build an archive of the influential black women who were imperative to the development of feminism, as all you ever hear are women like Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony.

Of course, we cannot have successes without limitations. The first limitation of my archive regards the biographies of the women I chose to feature. The lives of these women are beyond spectacular, and a simple paragraph would in no way do them justice, but I didn’t want to write a whole novel in my archive because, at the end of the day, I wanted my audience to be engaged with the content, and a wall of text might’ve deterred them from my project. Along those same lines, I wanted to highlight these women and their amazing contributions—but I didn’t want to speak for them; I didn’t want to tell their stories for them. This is something I struggled with a lot when constructing their biographies, because in the end, I want my archive to capture my audience’s attention and then want them to do their own research on their own, which will hopefully lead them to the works that these 5 exceptional women published themselves.

If I had more time to work on my archive, I’d bring out all the stops. I would construct a timeline for all the notable events that happened in each of the 5 womens’ lives, but given the time frame, it wasn’t plausible this time around—though a girl can dream. Furthermore, if given more time, I would also go into more detail about the effects they had on feminism and intersectionality they had, as it was remarkable what they did during a time period where just about everyone wanted to silence them. Overall, to say I learned a lot when building this archive is an understatement. Not only did I learn about the technical aspects of this archive like copyright and license terms, and how to make a picture bigger in the shortcode, I also learned how formatting and content contributes massively to the narrative one is trying to portray. If I was to use timelines instead of gallery sliders, my archive would tell a completely different story. Finally, the biggest thing I learned about was diversity and how overlooked it is. No one blinks at eye at the fact that the major women mentioned in the development of feminism are namely all white. You really have to look beyond what society has conditioned us to think to realize the greatness in these monumental revolutions, which is a lesson learned from building this archive that I know I will keep.

References

Alice Walker. (2018, February 27). Retrieved from https://www.biography.com/people/alice-walker-9521939

Angela Davis. (2018, January 19). Retrieved from https://www.biography.com/people/angela-davis-9267589

Audre Lorde. (2017, January 04). Retrieved from https://www.biography.com/people/audre-lorde-214108

Bell Hooks Biography. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.notablebiographies.com/He-Ho/Hooks-Bell.html

Branigin, A. (2018, March 16). These Are the Women of Color Who Fought Both Sexism and the Racism of White Feminists. Retrieved November 30, 2018, from https://www.theroot.com/these-are-the-women-of-color-who-fought-both-sexism-and-1823720002

Ortega, M. (2006). Being Lovingly, Knowingly Ignorant: White Feminism and Women of Color. Hypatia,21(3), 56-74. doi:10.1353/hyp.2006.0034

Worthen, M. (2018, July 17). Tarana Burke. Retrieved from https://www.biography.com/people/tarana-burke

Why Feminism Fails Black Women. (2018, March 06). Retrieved from https://youtu.be/t9KMtf_e_ew

This archival exhibit was created by Dara Sostek in Literature and Digital Diversity, Fall 2018.