Introduction

“An Illustrated Monthly Devoted to Literature, Science, Music, Art Religion, Facts, Fiction and Traditions of the Negro Race”. –The Colored American Magazine

The Colored American Magazine, published between 1900-1909, was the first American monthly-periodical that displayed African American culture. Through art and literature, the magazine depicted what it meant to be African American culturally, in contrast to the previous publications relating to the abolitionist movement. In terms of literature, one of the magazines most illustrious writers was Pauline E. Hopkins, who was succeeded by Fred R. Moore (under Booker T. Washington’s governance). As an editor, Hopkins published short stories, novels, biographical essays, critiques of racial oppression in Jim Crow America, as well as pieces for the Women’s section. Unfortunately, the magazine was re-bought by Fred R. Moore and published in New York. The focuses of the publications shifted to African American achievements in the business sector, which ignored the initial intent of utilizing the publication to craft political arguments through literature.

In addition to the literary aspects of the publication, as the magazine was based out of Boston, several business and marketing campaigns played a prominent role in the reproduction and sales of the magazine. Advertisements were often placed in the first few pages of the magazine to encourage readers to subscribe to the monthly publications and purchase from local sellers. Despite the economic standpoint for these advertisements, often times the ads were discreet racial arguments, discriminatory, and featured businesses that did not reflect the African American community from a cultural or literal standpoint.

This archive places these advertisements into display because they are generally omitted when discussing the different aspects of the magazine. I received the materials for this archive from the Digital Public Library of America (DPLA), and Yale University Libraries. Within the archive, you will find three rows of ads relating to money/finance, hair, and businesses that are present throughout the first few pages of the magazine issues. After performing research on the ads, I discovered that an audience of white Americans represented 1/3 of the readers, which informed my analysis regarding the contradicting ad material to the magazine’s purpose. Finally, following the ad analysis, there is the source material that accompanies my research.

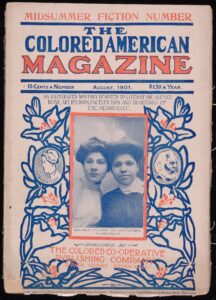

The Colored American Magazine Publisher: Moore Pub. and Print. Co. Genre/Subjects: Magazines/periodicals, Poems, Advertisements, African Americans Volume: Vol. 3, no. 1 Curatorial Area: Beinecke Library https://brbl-dl.library.yale.edu/vufind/Record/3999324

The Colored American Magazine Publisher: Moore Pub. and Print. Co. Genre/Subjects: Magazines/periodicals, Poems, Advertisements, African Americans Volume: Vol. 3, no. 2 Curatorial Area: Beinecke Library https://brbl-dl.library.yale.edu/vufind/Record/3999324

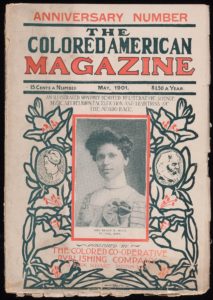

The Colored American Magazine Publisher: Moore Pub. and Print. Co. Genre/Subjects: Magazines/periodicals, Poems, Advertisements, African Americans Volume: Vol. 3, no. 3 Curatorial Area: Beinecke Library https://brbl-dl.library.yale.edu/vufind/Record/3999324

I began by adding (to the left) a gallery of some of the covers of the magazine. While Pauline Hopkins was in control of the publications, the magazine featured women of color, along with a portrait of Phillis Wheatley and Frederick Douglass beside them. These covers emphasized Hopkins intended concentration on women and African American leaders. On the right, you will find a letter written by Ms. Hopkins to J. Max Barber (editor of “Voice of the Negro”), where Hopkins is warning Barber of the future of Voice of the Negro in relation to Booker T. Washington’s rule over the magazine, because of her experience with The Colored American Magazine. Although all of the ads in this archive are published in issues when Pauline Hopkins was the editor, I thought that this letter was important to include to prove that when Hopkins wasn’t the head editor for the magazine she was still devoted to the publications. In addition, I also believe that it is important to include the letter in reference to the shifts in changes in the intention of the magazine when Fred R. Moore took control.

Advertisements

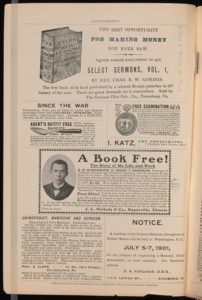

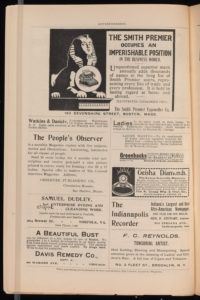

The Colored American Magazine Publisher: Moore Pub. and Print. Co Genre/Subjects: Magazines/periodicals, Poems, Advertisements, African Americans Volume: Vol. 3, no. 1 Curatorial Area: Beinecke Library https://brbl-dl.library.yale.edu/vufind/Record/3999324

The Colored American Magazine Publisher: Moore Pub. and Print. Co Genre/Subjects: Magazines/periodicals, Poems, Advertisements, African Americans Volume: Vol. 3, no. 1 Curatorial Area: Beinecke Library https://brbl-dl.library.yale.edu/vufind/Record/3999324

The Colored American Magazine Publisher: Moore Pub. and Print. Co Genre/Subjects: Magazines/periodicals, Poems, Advertisements, African Americans Volume: Vol. 3, no. 1 Curatorial Area: Beinecke Library https://brbl-dl.library.yale.edu/vufind/Record/3999324

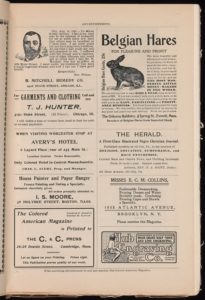

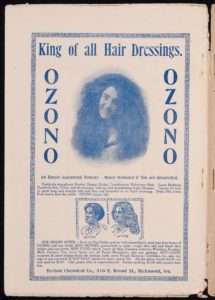

The Colored American Magazine Publisher: Moore Pub. and Print. Co Genre/Subjects: Magazines/periodicals, Poems, Advertisements, African Americans Volume: Vol. 3, no. 3 Curatorial Area: Beinecke Library https://brbl-dl.library.yale.edu/vufind/Record/3999324

The Colored American Magazine Publisher: Moore Pub. and Print. Co Genre/Subjects: Magazines/periodicals, Poems, Advertisements, African Americans Volume: Vol. 3, no. 3 Curatorial Area: Beinecke Library https://brbl-dl.library.yale.edu/vufind/Record/3999324

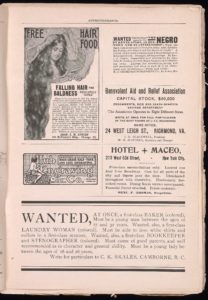

The Colored American Magazine Publisher: Moore Pub. and Print. Co Genre/Subjects: Magazines/periodicals, Poems, Advertisements, African Americans Volume: Vol. 6, no. 5 Curatorial Area: Beinecke Library https://brbl-dl.library.yale.edu/vufind/Record/3999324

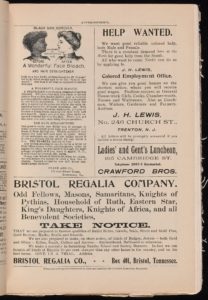

The Colored American Magazine Publisher: Moore Pub. and Print. Co Genre/Subjects: Magazines/periodicals, Poems, Advertisements, African Americans Volume: Vol. 4, no. 3 Curatorial Area: Beinecke Library https://brbl-dl.library.yale.edu/vufind/Record/3999324

The Colored American Magazine Publisher: Moore Pub. and Print. Co Genre/Subjects: Magazines/periodicals, Poems, Advertisements, African Americans Volume: Vol. 4, no. 3 Curatorial Area: Beinecke Library https://brbl-dl.library.yale.edu/vufind/Record/3999324

The Colored American Magazine Publisher: Moore Pub. and Print. Co Genre/Subjects: Magazines/periodicals, Poems, Advertisements, African Americans Volume: Vol. 4, no. 3 Curatorial Area: Beinecke Library https://brbl-dl.library.yale.edu/vufind/Record/3999324

AD Analysis

Money/Finance:

On the surface, the first ad that I chose to include in the archive (Vol. 3, no. 1, AD 1) seemed like a relatively positive one selling “Select Sermons Vo. 1” from Rev. Chas B. W. Gordon. However, the ad is asking for agents to sell to book as the “best opportunity for making money”, without highlighting the religious context or why the Reverands work is in “great demand”. Instead, the sermons are published as a profiting device for agents, in which the agents are not typically African Americans. Similarly, the second ad that I chose (Vol. 3, no. 1, AD 2) sells Belgian hares as another money making scheme to profit off the animals if the consumer sends in $25. While “a third or more of the magazine’s readers were white patrons” (coloredamerican.org), Blacks were not “profiting” from these proposed sales.

Hair:

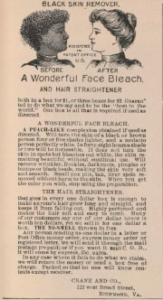

Personally, I believe that the hair ads displayed in the majority of the magazine issues were mainly arguments relating to racial discrimination. For instance, in the second row, the first ad (Vol. 3, no. 3, AD 1) is selling boxes of “Ozono”, a hair product that is supposed to transform “Nappy, Kinky, Troublesome hair” too ” Long, straight, soft, and fine, and beautiful hair”. Typically, to accompany the hair products, the ads also sold “Skin refiner” to turn “black skin bright”. The second ad that I chose (Vol. 3, no. 3, AD 2) I think clearly depicts a racist and discriminatory argument. The highlighted portions of the ad are “Black skin remover, A wonderful face bleach, and hair straightener”, along with a “before and after” shot of an African American transformed into a white woman. In a magazine that wants to make a political argument for blacks through literature and showcase African American culture, these hair ads contradict the intent of the periodical. These hair ads touch on a cultural identity marker for African Americans through a negative light which will lead African American readers to believe that their hair texture is subordinate to the “straighter, longer, and beautiful hair”.

Business:

As for the ads relating to business, they are also similar to the hair ads in the manner that they are advertising for ethnic and racial modifications. For instance, the first ad (Vol. 4, no. 3, AD 1) that I examined includes a bolded title to highlight the purpose of the advertisement “A Good Complexion”. Following the title, the description states ” How to acquire it without drugs or cosmetics. A little book telling just how and what to do”. This 25 cent book was advertised to teach the intended audience of African Americans how to obtain a “good complexion”, that would’ve been considered superior and acceptable during the earliest 20th century. In relation to the money/finance ads, the hair business ads are less subtle in their arguments in order to persuade more African American readers to buy from the businesses while simultaneously demolishing their culture. Furthermore, I also chose to include the ad relating to a “free gold-plated watch” (Vol. 4, no. 3, AD 3), that was featured in most magazines to encourage readers to purchase the subscription. I thought it was interesting that the ad notes, “We want only honest persons and those meaning business to accept this offer”. Considering that whites represented 1/3 of the audience I think this ad was specifically directed at people who were financially stable and would be able to profit off of the magazine.

Conclusion

After compiling the materials for this archive and performing research on the magazine, I was able to take away a different perspective on publication and audience. When I learned that Pauline Hopkins intended for the audience to be African Americans and the purpose of the magazine was to reflect African American culture through political arguments in literature, I thought that this was a phenomenal idea, especially for the earliest 20th century America. However, I do believe that the advertisements did contradict the uplifting intentions of the magazine because they were degrading African Americans and proposing racial and ethnic modifications. With that being said, the ads were able to entice a new white audience who were able to subscribe to the periodical and keep the magazine running. In the end, I believe that everyone profited off of this magazine, either from knowledge about African American culture or financially from investing in the magazine.