Introduction

On the surface, race appears as a simple category to quantify—the color of one’s skin, the box one circles on the census, even the percentage that appears on an at-home DNA testing kit. But the reality of one’s racial identity is hardly objective. This archive outlines the stories of individuals who chose to“pass” as a different race, or as a portion of their racial background, often in pursuit of societal advancement that their given race prevented them from obtaining. The decision to accept or deny any aspect of one’s identity is a complex and difficult decision, and this collection aims to educate the public on those challenges and intricacies faced by those of multiracial backgrounds in both the era of segregation and today.

2875

Organization

This archive is structured around the environments and dominant factors in each individual’s decision to pass—including emancipation, education, and employment. This division is not intended to claim that these are the sole or even intentional reasons to racially pass, but rather to thematically organize stories that share similar domains. To best tell the narrative of both the individuals and the broader social climate they lived in, I collected individual and family portraits, illustrations, and newspaper clippings. I aimed to represent both the singular person and the communities they were joining or leaving.

2963

Privilege & Personal Connection

In tracing the loss and gain of these individuals identities, I was also hoping to uncover revelations and discoveries of my own. I struggle with the quantification of my race with every form I fill out—seeing the tidy bubbles for “black” and “white” and losing a place to record their overlap. As a biracial women with a fair complexion and face full of freckles inherited from by father’s European descent, it is easy to lose my mother’s Afro-Mexican heritage when you view race at pure face value.

People say they can see my natural curls in the slight wave of texture in my hair, or in the dark pigments hidden on my body as if my skin has become a treasure map of my ancestry, but even I acknowledge the stretch. Next to my mother and sister, I appear unequivocally white. I have the opportunity to pass between spaces of black and white culture, and the privilege to never have to pick between them. But that doesn’t mean others haven’t decided for me. Years of correcting my school officials after they recorded me as “white” in my registration documents have shown me there is a rich and never-ending obsession with choosing the identity of others without their consent. This archive documents those that reversed that phenomenon and claimed their own autonomy in their identity, and the result of those decisions.

Emancipation

Some of the earliest cases of racial passing come from descendants of mulatto slaves trying to escape from their enslavement. These children were often fathered by their white masters, which led to their fair skin and resemblance to other white children. Below is the story of Ellen and William Craft, a married couple who escaped from southern Georgia when Ellen passed as a white male.

Ellen & William Craft

Ellen Craft’s race was classified as “quadroon,” referring to one quarter African descent and three-quarters European ancestry. She was the daughter of a biracial slave and her white master, Major James Smith, and was eventually given to the master’s daughter to rid her from the household and her half siblings. She moved to Macon, Georgia as a house servant with Eliza Smith. It was there she met William Craft—an enslaved carpenter whom she would marry in 1846.

The two began planning their escape in 1848. Ellen cut her hair and wore men’s clothing purchased by William using his savings from his carpentry work. William masqueraded as her personal servant as the two took a train and boat to the North. Once they settled in Boston, they began to share the story of their escape and published a book titled “Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom,” as shown in the gallery on the right.

Education

Many of the first African American students in higher education classrooms and campuses were quietly integrated long before this avenue was open to non-white students. The individuals shown below were among the first black students to attend American universities by passing as white.

2387

Anita Hemmings

Hemmings was the first African-American student to graduate from Vassar College in 1897. She grew up in Roxbury, Massachusetts and returned to Boston to work as a librarian at the Boston Public Library. After marrying Dr. Andrew Jackson Love, a doctor also passing for white in 1903, the two chose to continue their lives as white. Their daughter, Ellen Hemmings, became the second African-American student to graduate from Vassar in 1927—unaware of her own racial identity.

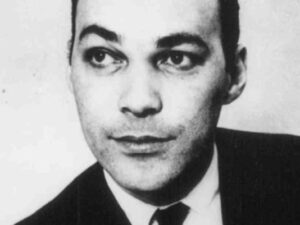

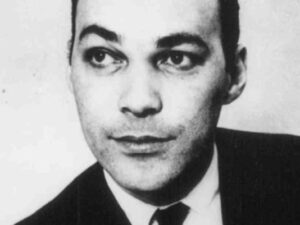

Harry S. Murphy

Murphy attended the University of Mississippi in 1945 as a result of the Navy College Training Program. When he enlisted, his officer marked his race as “white” due to his fair-skin and wavy brown hair. This transferred over in his application to Ole Miss, and was never questioned. The university was never fully integrated until 1962 after a series of violent riots when black student

James Meredith tried to attend. Unlike other individuals, his passing was accidental. After his Navy program ended, he transferred to the historically black college Morehouse College.

Roxborough was the first African-American student to live in a dormitory at the University of Michigan in 1933. Roxborough came from a wealthy black family, and grew up her with life in the spotlight of tabloids and magazines. Despite her light skin, she had no way of passing while still retaining her family name. In college, she often discussed with Langston Hughes “her dreams, and wonder whether or not it would be better for her to pass as white to achieve them” (Hughes). Upon graduation, she decided to give her acting dream a go. She shed her family name and became “Mona Manet,” passing as a white model with dyed red hair. She refused to see her family in Detroit again, in fear of jeopardizing her new identity.

Elsie Roxborough

Employment

In an effort to escape prejudice or insert one’s self in spaces where their presence was not yet defined, some individuals chose to pass as a different racial identity in the workplace.

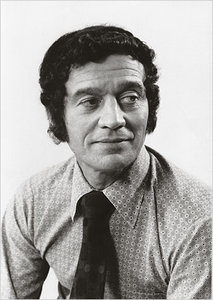

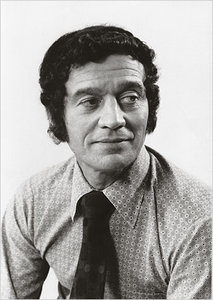

Anatole Broyard

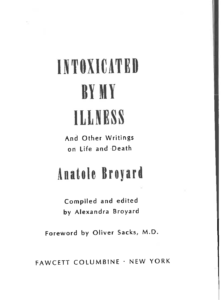

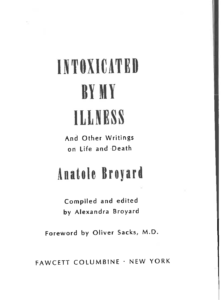

In the first line of his book, “

Intoxicated by My Illness,” Broyard declares: “I want to begin by confessing that I’m an impostor.” The famed writer and literary critic wasn’t referring to his hidden racial identity, but those details would still be revealed by Henry Louis Gates, fellow literary critic and genealogy historian, in his essay “White Like Me.” Broyard was born of Creole descent, and chose to conceal his race in order to advance as a writer in Brooklyn, NY. As Gates claimed, “he did not want to write about black love, black passion, black suffering, black joy; he wanted to write about love and passion and suffering and joy.”

“Intoxicated by My Illness” by Anatole Broyard

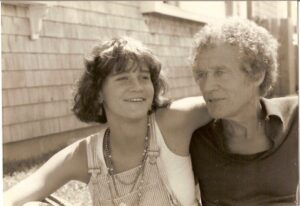

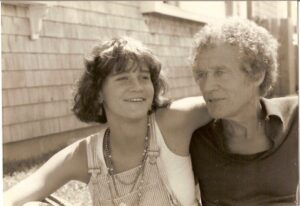

Anatole & Bliss Broyard

Anatole’s secret wasn’t revealed until his death bed when his wife told his two children of their father’s true racial background. His daughter, Bliss, grew up to write a

book documenting the experience: of discovering this secret, discovering a new family, and discovering her own identity. While Allyson Hobbs, professor and researcher of racial passing, documents the loss of community involved in passing in her book

A Chosen Exile, Broyard documents the growth.

Contemporary Passing

As illustrated above, race is a part of one’s identity that does not always neatly fit into the predefined bounds society has set for it. It can be an acceptance, a rejection, a reckoning of one’s past and present. It remains a privilege, however, to be able to have autonomy over the categorization of one’s self. It is also a privilege to claim to “transcend” one’s identity, as in the case of controversial figure Rachel Dolezal who claims to identify as black, although she was born into a white family in rural Montana with no black ancestry. Dolezal’s claims reopen the discussion of how does one build their identity as white or black, and revealing the several shades of complexity in trying to define one’s self.

Credits

Anita Hemmings

Photographs from the

Vassar College Archives and Special Collections.

Harry S. Murphy

Photograph from the

Clarion Ledger.

Elsie Roxborough

Photograph from the

University of Michigan Archives.

Anatole Broyard

Photographs from Bliss Broyard

―This archival exhibit was created by Vanessa Gregorchik in Literature and Digital Diversity, fall 2017.