Special thanks to Sarah Connell, Ash Clark, and Micah Weston for helping me (try to) learn Python for my scraping journey! There was no way I could’ve pulled this together without all of your help and support.

Introduction

I grew up in rural Upstate New York, just below the Adirondacks. In case you’re unfamiliar with the area, it’s similar to living in the American South but with lots and lots of snow in the wintertime. Given the nature of where I lived, I was surrounded by country music for most of my young life. I enjoyed the majority of it, but as I grew older I began to realize a shift in the styles of country music that I’d hear. Instead of hearing The Chicks’ “Cowboy Take Me Away” like I was used to, songs like Zac Brown Band’s “Chicken Fried” or Toby Keith’s “Beer For My Horses” would play constantly on the radio. I’d always wondered what had happened to the music I used to love, and didn’t get anything close to an answer until I had nearly finished high school.

Music has historically been used as an outlet for a particular generation of people to express their thoughts, from anti-war sentiments with rock of the ’60s and ’70s, to antiracist ideals with modern-day rap and hip-hop. Country music is no exception. The most memorable songs of the mid-to-late 1900s often discuss the lives of working-class Americans living in rural areas, like “Coal Miner’s Daughter” by Loretta Lynn and “9 to 5” by Dolly Parton, for example. While this theme is still seen in the country music of today, topics like beer, trucks, girls, and God seem to steal the show. Though often anecdotal in evidence, many point to the attacks on September 11, 2001 as the reason why country music shifted to its current beer-drinkin’, tractor-ridin’, all-American state. The patriotism embraced by the nation during the War on Terror, especially in rural areas, is reflected in many songs explicitly inspired by 9/11 — The Charlie Daniels Band’s “This Ain’t No Rag, It’s a Flag” and Toby Keith’s “American Soldier” to name two. Ironically, though songs like these position the United States as unified against terrorist forces (Boulton, 374), the blatant hyper-patriotism within them has caused a world of generalization, and turned many would-be country fans off to the genre as a whole.

Given the background describes above, my goal for this project was to explore the following research question using the R programming language and word2vec analysis:

Do the lyrics of American country songs reflect the general consensus that an increase in patriotism took place within the genre following September 11, 2001?

That is, do lyrics across the genre contain more words related to patriotism, war, and religion after 9/11 than they did in the years prior to the attacks? While it may seem that the answers to these questions are simply ‘yes’ or ‘no,’ through my research and the creation of my corpora I observed much more nuance that should be taken into account.

Methodology

The process of creating these corpora was much more involved than I ever anticipated. In order to compare the lyrics of country songs before and after 9/11, I needed to create two corpora. The first, which we shall call the Old Corpus, includes lyrics from country albums from 1950 to 2000. The second, which we can call the New Corpus, contains lyrics from 2002 to 2020. I used the Genius API to scape the lyrics I needed using John W. Miller’s GitHub client LyricsGenius, but ran into several hurdles along the way. After struggling with an inability to scrape due to issues with metadata formatting on Genius (as well as my general lack of knowledge of Python), I was eventually able to pull the lyrics through a combination running code that would search for and write lyrics by album and artist, and copy and pasting the lyrics into text files by hand. The code below is what I used to pull multiple albums at a time. It was crafted by Ash Clark — without eir help I am certain that I would not have been able to complete this project.

names = [‘[insert album here]’,'[insert album here]’]

for thisalbum in names:

album = genius.search_album(thisalbum, “[insert artist name here]”)

album.save_lyrics(extension=’txt’)

Initially, I focused on pulling lyrics from only the most popular artists from each period of time, but after realizing how many more lyrics would be necessary to yield productive results I chose to pull lyrics from prominent artists’ entire discographies. Unfortunately, the corpora were not as large as I would have liked due to the time constraint and the issues explained above, but the Old Corpus and the New Corpus’ models were trained in RStudio with ~811,000 and ~844,000 words, respectively. Rankings from Taste of Country, The Boot, and Billboard were instrumental in choosing what appeared to be country music’s most important artists (and their albums) in the creation of the corpora.

Data and Analysis

Given the way songs are written, there is no single word that allows us to analyze the effects of 9/11 on country music (something like ‘patriotism’ is ridiculously on-the-nose). It is for this reason that I chose to split my analysis of my corpora into a few sections, making queries based on words that fall into one of three categories: religion, nationalism, and military, topics that are generally considered to be found together especially in conversations about rural areas. Looking at several words in each of these categories and finding which terms are closest to them in both the Old Corpus and New Corpus allows us a firmer grasp on the common contexts in which these words are found. Significant change in the contexts from the Old to the New Corpus may tell us a bit more about the contributions post-9/11 patriotism made on the genre.

Religion

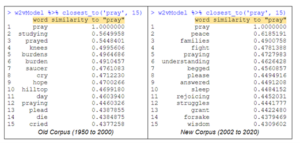

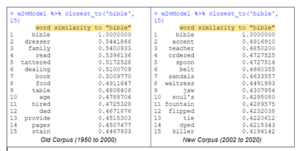

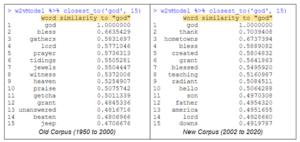

For this section, I took a look at three terms: ‘pray,’ ‘bible,’ and ‘god.’ While these terms seem rather general and somewhat trivial in the broader conversation of religion’s place in country music, just looking at the 15 terms most similar to these in both the Old and New Corpora offered some intriguing results. It is important to note that country music has seen the rise and fall of different uses of religion in songwriting across the decades. As I saw during the process of building my corpora, many artists in the 1950s and 1960s would often release hymn albums or records where they’d sing gospel in specific. At the end of the 20th century and into the 2000s and 2010s, Christmas albums were much more common than hymnals, a shift that most likely contributed to what is analyzed below.

Firstly, for ‘pray’ in the New Corpus we see that ‘peace,’ ‘families,’ and ‘fight’ are the top three most similar terms, whereas in the Old Corpus the top words relate more directly to the act of praying itself (‘studying,’ ‘prayed,’ and ‘knees’). ‘Struggles’ and ‘forsake’ are much lower on the list in the New Corpus, but they still contribute to the connection these words have to the moment following the start of the War on Terror, as well as the war’s continuation.

The results for ‘bible’ are a bit more difficult to parse and find meaning in. It seems that the terms most similar to ‘bible’ in the Old Corpus are related to family, providing for said family, and reading the book itself. Those in the New Corpus do not offer such clarity. When making queries to try and omit words such as ‘accent’ and narrow the field to just ‘bible’ words about religion, I was left with terms of cosine similarities <0.2, which it have decided to omit as they are too vague to offer much solid ground for analysis.

Looking at the terms most similar to ‘god’ is also quite interesting, providing somewhat similar results to what we saw with ‘pray.’ In the Old Corpus, ‘god’ seems to be found in contexts where religion is spoken about rather broadly. Words like ‘bless,’ ‘lord,’ and ‘prayer’ reflect this, while those like ‘gathers,’ ‘tidings,’ and ‘witness’ point toward contexts where going to a church service is sung about, or perhaps the birth of Jesus Christ is referenced (both of which may be the result of the common hymn records I mentioned earlier). In the New Corpus, ‘god’ appears to be referenced in contexts where they are being thanked for having blessed an individual or a group of people (numbers 2 and 7), or maybe having been a part of a religious upbringing (‘hometowns’ and ‘teaching’). The result I found most interesting here was the inclusion of ‘america’ on the list. Though it doesn’t appear here in the Old Corpus, the phrase ‘God Bless America’ was common in the 20th century because of the song by the same name. This use in the New Corpus may point toward a new focus on religion’s importance to the nation at the start of the 21st century, which is discussed in the next section.

Nationalism

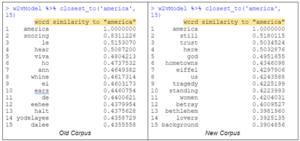

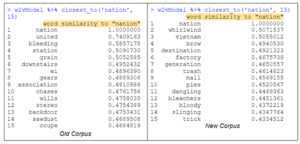

To analyze nationalist tendencies across my corpora (to an admittedly very small extent), I chose queries that would allow me to see the changes that may have taken place in the contexts for the terms ‘america’ and ‘nation.’

When analyzing the first term, one will immediately notice the strange set of words apparently similar to ‘america’ in the Old Corpus (‘le,’ ‘ho,’ ‘eehee,’ etc.). I believe this is the result of grouping of songs from an artist who yodeled in many of their works, though what it has to do with America I cannot infer. When making the query “w2vModel %>% closest_to(~’america’-‘le’,15)” the results are all <0.3 cosine similarity, but terms include ‘her,’ ‘snoring,’ ‘cope,’ and ‘heartbeat.’

To me, the most interesting takeaways from this query of ‘nation’ use are the Old Corpus’ inclusion of ‘united’ and ‘bleeding,’ and the New Corpus’ ‘vietnam,’ ‘bloody,’ and ‘slinging.’ Interestingly both of these data sets seems to offer a general focus on war, as well as what I believe may be discussion of rural/blue-collar life given the presence of terms like ‘downstairs,’ ‘gears,’ ‘association,’ and ‘backdoor’ in the Old Corpus and ‘factory,’ ‘generation,’ ‘trash,’ and ‘mall’ in the New Corpus.

Military

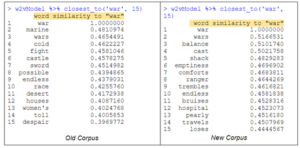

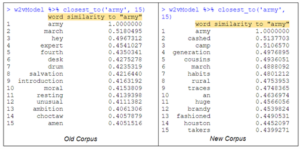

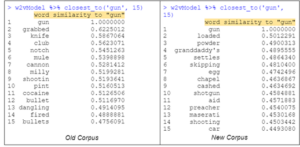

As the title may suggest, this section is concerned with the queries I made for terms relating to warfare. Specifically, I analyzed use of the terms ‘war,’ ‘army,’ and ‘gun.’ Each of these is rather broad and somewhat blunt, which was a decision I made in order to avoid being too specific for my corpora (the terms ‘terror’ and ‘terrorist,’ for example, produce no results).

Overall, the results I got from my military-related queries were interesting in what they seemed to lack: differences across the corpora. When looking at these data, it seems that songs from the Old Corpus were focused on the more general aspects of war in the cases of the three terms queried. It does seem, though, that songs from the Old Corpus speak to war as a concept whereas the New Corpus offers what one may consider to be a more personal approach to the topic with words like ‘bruises,’ ‘hospital,’ ‘cousins,’ and ‘granddaddy’s.’

Conclusions

Given the relatively small scale of this project, it is difficult to offer any definitive answer to my initial research question, but based on the data presented above I can confirm to a certain extent that country music post-2001 takes a slightly more personal approach to the concepts of religion, war, and patriotism. While country music from 1950 to 2000 certainly has its fair share of emotionally-charged songs, including those relating to war and religion, given the prevalence of the terms shown in the previous sections one can reasonably state that country music of the 21st century is more focused on these areas than it was in preceding years. It goes without saying that much more research can be done into the questions I presented in this project. It is my hope that the preliminary work here allows for the questions to be considered on a much broader scale, perhaps with a more comprehensive method of pulling lyrics for analysis (and perhaps a lyric database offering more accurate lyrics than the fan-contributions of Genius).

Reflections & Looking Forward

A point I think is crucial to make comes from Andrew Boulton’s ‘The Popular Geopolitical Wor(l)ds of Post‐9/11 Country Music, Popular Music and Society’:

“…country music songs do not exist in a vacuum, and that meanings are made both inside and outside the text (O´Tuathail ‘‘Condensing’’). Expectation matters; context matters; lyrics do not speak for themselves. The meaning of the Dixie Chicks’ successful Vietnam-themed song ‘‘Travelin’ Soldier’’ (2003), for example—conceivably glorifying the bravery and sacrifice of a young soldier, in a similar way to Trace Adkins’s reverential ‘‘Arlington’’ (2005)—bears re-reading in light of what we know about the politics of the song’s performers.” (Boulton 375)

Context is ridiculously important when considering song lyrics, especially in dealing with conversations rooted in politics. While Word2Vec modeling offers a glimpse into the contexts individual lyrics are found in, we unfortunately lose the ideological contexts of these artists in the process. As indicated in the Boulton quote above, certain artists may use very similar words in their lyrics, but the meanings may be completely opposite rather than contributing to the same trend.

If future work is to be done on this question using textual analysis, looking at individual country artists’ takes on the aftermath of 9/11 and the War on Terror in general may provide some helpful context. Additionally, looking into other potential causes for the patriotic shift seen in the genre would add dimensions to studies. Perhaps the Great Recession contributed to some of the sentiments seen in country music of the mid 2000s, and maybe the end of the Recession contributed to the party-oriented country music we see nowadays from artists like Florida Georgia Line.

My love for certain types of country music hasn’t changed. If anything, I’ve grown even fonder of the genre as a result of my research. Each artist has something to add to the genre as a whole, and while whether or not September 11, 2001 played a direct role in that creative expression for artists overall, I hope that the data presented in this project has helped make evident that a shift has taken place, one that should be examined further.

Works Cited and Further Readings

Boulton, Andrew. (2008) The Popular Geopolitical Wor(l)ds of Post‐9/11 Country Music, Popular Music and Society, 31:3, 373-387, DOI: 10.1080/03007760701563518

Carraway, Katherine. “A Frustrated Lifelong Fan: Country Music Must Stop Pigeon-Holing Itself: Opinion.” The Tennessean, Nashville Tennessean, 7 Jan. 2020, www.tennessean.com/story/opinion/2020/01/07/county-music-pigeon-holed-after-911/2803772001/.

Miller, John W. “Trucks and Beer 🍺.” John W. Miller, 7 Feb. 2018, www.johnwmillr.com/trucks-and-beer/.