The Ignorance of an Identity: Authors with Ignored Queer History

The goal of this archive is to shed light on a topic that, until recent decades, has been considered a major taboo: queer people (I use the term “queer” here as an umbrella term for those in the LGBTQ community, as the people I will go on to discuss in my archive did not give themselves any labels). Queer people have been here for a very long time, but those sides of them were suppressed and hidden from history because of their implications in society. In making my archive, I first did some preliminary research on famous queer authors. To my surprise, I found some very well known ones that I never would have guessed were queer – those parts of their identity have been erased from common knowledge. To illustrate this point, I looked at biographies from the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries written about these authors. I found instances where the biographers would refer to people (of the same gender) in the authors’ lives as “friends,” and then I found references to those people in the authors’ works that demonstrated a romantic or sexual relationship, whether very clear or able to be interpreted. Additionally, I added some instances where authors express queer desire more outright. This archive is here to highlight the erasure of queer identities from history and call readers to acknowledge this aspect of history.

I’ve organized my information about each other chronologically; I wanted to highlight the fact that well-known queer authors have persisted throughout history.

Lord Byron (1788-1824)

“Another friendship ran alongside this. In July 1807, Byron wrote to Elizabeth Pigot of one who ‘has been my almost constant associate since October 1805. His voice first attracted my attention, his countenance fixed it, and his manners attached me to him for ever.’ He was a young man named Edleston, who was one of the Cambridge choristers: two years younger than Byron, ‘nearly my height, very thin, very fair complexion, dark eyes, and light locks.’ Their acquaintance… began by his saving Edleston from drowning.

…At any rate, the Edleston friendship became a very sentimental one. The chorister gave him a cornelian heart as a keepsake…”

– Byron by Ethel Colburn Mayne (pages 90-91)

“The Cornelian” poem by Lord Byron

Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882)

“Perhaps thy lot in life is higher

Than the Fates assign to me,

While they fulfill thy large desire,

And bid my hopes as visions flee.

But grant me still in joy or sorrow,

In grief or hope, to claim thy heart,

And I will then defy the morrow

Whilst I fulfil a loyal part.”

Drawing of Martin Gay in the journal of Ralph Waldo Emerson, accompanied by poem (page 70)

Walt Whitman (1819-1892)

“In Washington, Whitman’s lifelong habit of intimate association with ‘powerful uneducated persons’ (which in the New York days enabled him to find comrades among the omnibus drivers and ferry-boat pilots) led him into friendly relations with many of the drivers and conductors of the street-cars. His intimacy with one of these men was so typical an example of the comradeship which is celebrated in the section of Leaves of Grass entitled ‘Calamus’ that it deserves special mention.

Peter Doyle was born in Ireland in 1874, and came to this country in infancy with his father, a blacksmith, who settled in Richmond, Va. Entering the Confederate army as a mere boy, he served throughout the war until he was paroled in Washington, where he obtained work as a street-car conductor. In this position, soon after the war, he met Whitman, who was a passenger on his car. In his own account of the meeting Doyle says: ‘We felt to each other at once…. He did not get out at the end of the trip,—in fact, went all the way back with me…. From that time on we were the biggest sort of friends…. Walt rode with me often at noon, always at night…. It was out practice to go to a hotel on Washington Avenue after I was done with my car. Like as not I would go to sleep,—lay my head on my hands on the table. Walt would stay there, wait, watch, keep me undisturbed, would wake me up when the hour of closing came…. In the afternoon I would go up to the Treasury Building, and wit for him to get through if he was busy. Then we’d stroll out together, often without any plan, going wherever we happened to get. This occurred days in and out, months running.’

This close companionship lasted until 1872, when Doyle entered the service of the Pennsylvania Railroad, by which he is still employed as a baggage-master. His friendship with Whitman continued until the latter’s death, and many and frequent letters passed between them.”

– Walt Whitman by Isaac Hull Platt (pages 56-58)

One page of poems in the “Calamus” section of Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass.

Emily Dickinson (1830-1886)

“To own a Susan of my own is of itself a bliss…”

– Unpublished manuscript of Emily Dickinson (Susan referring to Susan Gilbert Dickinson)

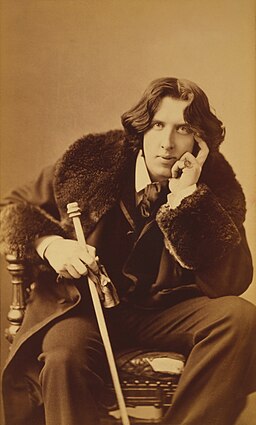

Oscar Wilde

“The next entry in the record, Wilde’s celebrated letter that was afterwards to be used in evidence at the Old Bailey, shoes that a new stage had been reached in their [Wilde and Alfred “Bosie” Douglas’s] relationship:

It was addressed to ‘My Own Boy’ and bore the subscription ‘Always with undying love.’ It lyricised the sweetness Oscar found in his own boy’s lips,—red, rose-lead lips that had been made no less for the music of song than for madness of kisses… To complete the expression of his delight Oscar found a comparison between his Alfred and Hyacinthus whom Apollo loved so madly.”

– The Friendships and Follies of Oscar Wilde by C. Lewis Broad (pages 123-124)

Virginia Woolf (1882-1941)

“Many of the letters I have been privileged to see were sent by Virginia Woolf to Lady Nicholson, referred to in the following pages by her maiden and pen name of Vita Sackville-West… It is a piece of the greatest good fortune to me–though Virginia Woolf often bewailed it as the greatest ill-luck to her–that the two friends were so frequently prevented from meeting.”

– The Moth and the Star: A Biography of Virginia Woolf by Aileen Pippett (preface, page ix)

From Sackville-West to Woolf

Milan [posted in Trieste]

Thursday, January 21, 1926

I am reduced to a thing that wants Virginia. I composed a beautiful letter to you in the sleepless nightmare hours of the night, and it has all gone: I just miss you, in a quite simple desperate human way. You, with all your un-dumb letters, would never write so elementary phrase as that; perhaps you wouldn’t even feel it. And yet I believe you’ll be sensible of a little gap. But you’d clothe it in so exquisite a phrase that it would lose a little of its reality. Whereas with me it is quite stark: I miss you even more than I could have believed; and I was prepared to miss you a good deal. So this letter is just really a squeal of pain. It is incredible how essential to me you have become. I suppose you are accustomed to people saying these things. Damn you, spoilt creature; I shan’t make you love me any the more by giving myself away like this—But oh my dear, I can’t be clever and stand-offish with you: I love you too much for that. Too truly. You have no idea how stand-offish I can be with people I don’t love. I have brought it to a fine art. But you have broken down my defences. And I don’t really resent it …

Please forgive me for writing such a miserable letter.

V.

https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2016/03/09/a-thing-that-wants-virginia/

―This archival exhibit was created by Ciara McAloon in Literature and Digital Diversity, fall 2017.