Checking the “Other” Box

But it hasn’t always been this way. Being forced into only one racial category on official documents was all too common for multiracial people throughout all of American history up until very recently, despite there having always been multiracial people.

Changing the US Census

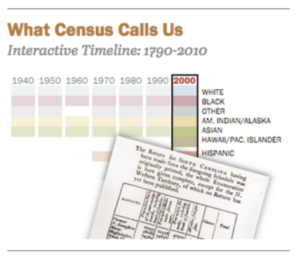

The way the US census has recorded data on race over it’s span of existence has evolved from year to year in an ever-growing attempt to better measure the demographics of such a racially diverse country. And with a country where race has played a central role in status both throughout history and even today, the census questionnaire reflects the way the politics of race has changed over the decades. “What Census Calls Us: A Historical Timeline” is a fantastic interactive resource that shows the comparison between the census today and versions used in the past. With a side-by-side visual layout, viewers are able to see the stark contrast in not only how America’s population became more diverse over time, but also how the government came to categorize different groups of people.

Early Versions of the Census

It wasn’t until 1850 when the option of “mulatto” was available, a very general term to describe anyone of mixed white and black parentage. This accounted for anyone with any trace of African blood – as well known by the “One Drop Rule”. In 1890, even more specific terms for mixed-race people were listed: quadroon – for those who had ¼ “black blood” – and octoroon – for those with 1/8 or less. The images below show a few examples of mixed race individuals who would fall under these categories.

Array

Instead, it was the census takers who came to your door to collect data, and it was the census takers who determined the race of the people they counted. In early censuses, federal marshals conducted these surveys. This changed in 1880 when government appointed enumerators who lived in the district they counted in were hired. This was done in an attempt for more accurate results, particularly on race, so that enumerators would be able to personally know each household, and therefore have a preconceived idea of race of each family.

Each census taker was different. Some counted mixed-race people according to their father’s race, other’s categorized them immediately with their minority group. With over 100 years of inconsistencies in census takers’ definition of race and their mistakes made due to false perceptions, the records are left devoid of accurate information about people of multiracial backgrounds.

The two letters are concerning mixed race African Americans during the early 20th century, and draw attention to the “One Drop Rule”. The newspaper article includes a headline addressing the momentous change to the census where the multiracial option was finally allowed.

Sends information on the Encyclopedia of the Negro and will send an article on the cultural persistence of Africanisms in Bahia for the journal Africa. Wishes Westermann's opinions on persons of mixed race in Brazil versus the United States: "I find it rather difficult, in short, to reconcile the anthropological conception of the Negro with the conception that prevails in the United States where, as you know, one drop of African blood makes a white man a Negro or, to use the census definition, 'a Negro is one who is known as such in the community in which he lives.'"

Park, Robert Ezra, 1864-1944

Westermann, Diedrich, 1875-1956

Includes bibliographical references (p. 165-185) and index.

Introduction -- Undoing the working definition of race -- The multiracial census -- Multiracial category legislation in the States -- Political commitments -- Growing racial diversity and the civil rights future.

Williams, Kim M., 1968

Shipping list no.: 99-0743-M.

Also available via Internet at the ERIC web site. Address as of 11/06/02: http://www.ed.gov/databases/ERIC%5FDigests/ed425248.html; current access is available via PURL.

Microfiche.

[Washington, D.C.] :

Supt. of Docs., U.S. G.P.O.,

[1999]

1 microfiche.

Schwartz, Wendy. https://id.loc.gov/authorities/names/no90026607

How Changing the Census Impacted American Society

Undoubtedly, this is no coincidence. It is likely that these populations had always been significant, but were only then getting the opportunity to self-report their identity and be recorded by the government accurately.

Not to entirely discount the rise of multiracial populations. In 1990, “Other” was the third fastest growing group in America. More recently, in 2013, 9.3 million identified themselves as being multiracial, about 3% of the country’s total population.

The changing of the US Census options also represents a societal shift, as the traditional norms are challenged. At first, the census only looked at free white people and enslaved black people. But as American demographics have changed, the census has adopted the new labels to fit, as well as reflecting social public opinions. The ban on interracial marriage, carried out by anti-miscegenation laws, was lifted in 1967. Public approval of interracial marriages skyrocketed from 5% in the 1950’s to 80% in the 2000s, likely contributing to the census alteration that allowed more than one race to be chosen. (The images in the gallery below depict a few examples of interracial couples even before this societal outlook was changed.)

Today, race is no longer just a fixed physical characteristic, but a more fluid concept of identity and culture that social scientists today believe is influenced by the current social and political thinking. The census had the power to define race into tight little boxes, and limit society’s perception of what these identities meant. The materials in the gallery on the left are a few examples of multiracial people getting to express their experiences and share their narratives. By opening up these boxes, the census now has less control over limiting racial identity, and mixed-race people can feel less constricted in their own identities. I am glad to have grown up in a time where I get to check all the boxes that define my identity, at the same time knowing that I don’t need to let these labels define who I am.

Ninomiya Studio: photographer

Array

Ninomiya Studio: photographer

Ninomiya Studio: photographer

Array

Ninomiya Studio: photographer