Ableism in Ethical Philosophy

What is Ethics?

Some of the earliest known philosophical musings, at least in Western Europe, involved asking what it meant to be a good person, what it meant to do good. In attempting to answer these questions over the centuries, many major figures have written a litany of books and essays attempting to create the one true ethical theory that provides a way to accurately and objectively make “good” decisions, each claiming the others fail to sufficiently consider base facts of the universe. The assumptions that each theory presents frames the philosophy as a whole, with some of the earliest thoughts on the matter simply focusing on what a good person would be, while others argue one should aim to for consequences that maximize utility, and others still claim everyone should adhere to some universal maxim. Despite these stark differences in ethical theory over the years, several assumptions are maintained across the different philosophers” beliefs, one of the most significant being that a “good” agent is a rational one, capable of making and acting on objective decisions. Under such a framework, it becomes unclear how these ideas would handle concepts such as mental illness and physical disabilities. As such, I sought out to investigate to what extent has the western ethical philosophies’ focus on capacity and ability influenced and been influenced by a lens of ableism?

Analysis Techniques and Strategies

Corpus Creation:

I collected various novels by significant western philosophers of ethical philosophy from Project Gutenberg, a free source of literature whose copyright has expired.

The following text files were downloaded and used for this research:

- Nietzsche: “Beyond Good and Evil”

- Kant: “Critique of Pure Reason”

- Kant: “Critique of Judgement”

- Kant: “The Metaphysics of Morals”

- Descartes: “Discourse on the Method of Rightly Conducting One’s Reason and of Seeking Truth in the Sciences”

- Aristotle: “The Ethics of Aristotle”

- Mill: “On Liberty”

- Mill: “Utilitarianism”

- Hume: “Principles of Morals”

- Plato: “The Republic”

In preparing the files for analysis, I removed Project Gutenberg’s introduction and metadata in the beginning, the copyright information at the end, any table of contents to avoid overemphasizing title words, and any format signifiers (such as “_” and “*” surrounding words). In doing so, the files I used for my analysis contained the body of the works listed above.

Word Vectors

This bulk of this analysis took advantage of Word Vectors, specifically the Word2Vec package in the R programming language, a technique that maps (space separated) words to a spatial representation. While the math behind this is relatively unimportant for this use case, the results of said math allow us to figure out the similarities and relationships between words. These relationships are based entirely on their usage within the corpus, allowing for analysis to focus on contextual meaning. Because of the context aware nature of word vectors, querying a trained model can reveal assumptions about and associations between terms that previously could only caught by an astute reader over a much slower period of time.

Research and Results

Initial Queries

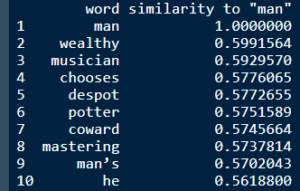

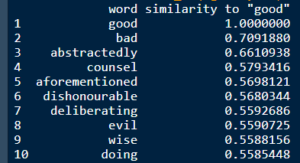

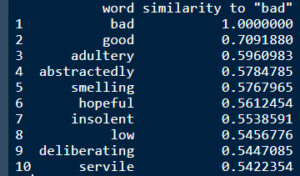

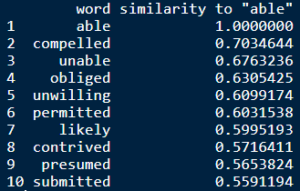

I started with single word queries, getting the 10 words most similar to “man”, “good”, “bad”, and “able” in the corpus.

The strong correlation between man and wealthy is interesting, and speaks to the general position of privilege most of these philosophies were written from. In general, “man” is used to refer to any given person / humanity as a whole. The fact that wealth is associated with the “typical” man indicates significant bias that, while not directly tied to ableism, lends itself to the argument that there are some damaging social assumptions made by the writers.

The association of “able” with both “compelled” at the very top as well as “obliged” and “unwilling” a couple spaces down in the list implies a strong assumption that ability is tied to choice. If one who is compelled to do good is considered roughly able to do good, the greatest barrier to being a moral agent becomes a matter of wills instead of a nuanced combination of conscience and ability. This stripping of “able” as it’s own potential significant consideration in action ignores the very real disabilities that should add significant depth to the meaning of ethics.

Joint Queries

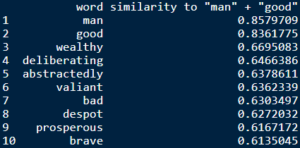

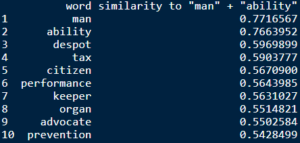

In order to dive deeper and confirm these initial findings, I conducted two joint queries: “man”+”good” and “man”+”ability”.

In the former, the “wealthy” was once again very similar, reinforcing the earlier idea that positions of power greatly shape western ethics, but more interestingly, “deliberating” rose in similar significantly when compared to “man” or “good” on their own. The focus on deliberation in ethics, while understandable as it is generally understood to be beneficial to think through one’s actions, emphasizes the focus on rationality that makes it easier to discredit the mentally ill or otherwise neuro-divergent since they often don’t meet society’s typical definition of rational (this can also be used to justify discrediting “hysterical” women, but that deserves it’s own conversation).

In the latter, the presence of “despot” and “citizen” emphasizes the association between positions of power / privilege and ability. A “man” with “ability” is associated with power and respect in society. This, of course, also describes nearly every major philosopher in the west, both in ethics and otherwise.

Targeted Queries

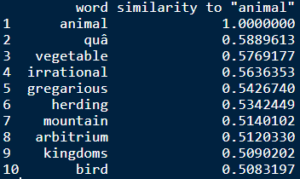

Much of moral philosophy often contrasts man to animals. In doing so, they posit that what deviates us from animals is some innate ability to be “good”. Such an argument would imply that animals, and those associated with animals, are incapable of goodness (and arguably equally incapable of badness).

The anthropocentrism of this stance is one worth investigating another time, but for the purposes of this post I queried simply for similar words to “animal” in an attempt to find trends related to ability.

The high relevance to “vegetable” and “irrational” are of note here. The association between “animal” and “vegetable” shows just how far apart the writers consider humans and animals. Animals are not simply less rational / not fully sentient beings, they are nearly objects (and food). The associations with “irrational” reinforces the aforementioned ableism in regards to neuro-divergence. It seems that if one were to act irrationally, based on the standards of those in power, they would be no better than food according to moral philosophers.

Conclusion

It seems clear after this analysis that ableism has had a significant effect on moral philosophy in the west and has been reinforced by said philosophy. The corpus has shown contextual similarity between goodness and rationality as well as ability while disparaging those that cannot always be “good”.

Future Research

Firstly, it would be beneficial to confirm this findings with a close reading of both the writings in the corpus and historical documents that may provide context to their theories. While a lens of ableism has proven to be significant in analyzing this branch of philosophy, the findings described in this post are preliminary and should be backed up by specifics. As such, the next step would involve a more hands-on approach, breaking down the corpus and comparing it to ableism both historically and through a contemporary perspective.

Further, this analysis has presented a few other conversations that would be worth investigating with word vectors, particularly power structures / authoritarianism, gendered issues, and anthropocentrism. While these topics were only briefly discussed here, these findings could provide a solid foundation to launch off of for further analysis.