Introduction

I learned about the Korean War twice. Once in Korea as a Korean. Once in America as an American. As an AP world history student, I understood that the war was in the context of a much bigger, grander war: The Cold War. It was about politics and ideologies. Communism. Capitalism and democracy. We studied the United Nations, Douglas MacArthur, and the 38th Parallel Line. It was considered ‘The Forgotten War’ because it succeeded World War 2, yet preceded Vietnam. It was nothing more than a test question- or at most, a short answer.

But it was a war that we still remembered. We didn’t call it the “Korean War” back home. It’s referred to as the 6.25 war or “육이오”. It’s set on a date because it serves as a reminder. That out of the year, there’s a time for Christmas or Easter. And there’s a time for this war. My grandmother told me how she remembers the war as a kid. Her house was a sanctuary while there were gunshots in the sky. To Korea, it wasn’t just a history. It was a memory. A memory that was very much alive in the world today.

The Archival Documents

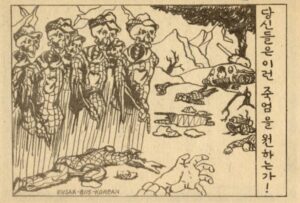

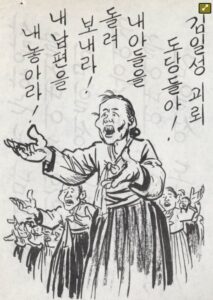

The following poems are remixes and inspirations from two primary documents in Digital Horizon. They depict anti-communists propaganda geared toward the North Korean army and population. The first one captures an army of dead spirits over the battlefield with a statement of how the North Korean Battalion suffered devastating losses. There’s a haunting question to the right that asks, “Is this the death you want?” The second propaganda was more domestic, capturing women protesting Ill-Song’s regime. They demand his government to release their husbands and stop killing their sons by sending them to this war.

It’s rather interesting to find these resources in Digital Horizon, a platform that serves as a resource database depicting life on the Northern Plains. But regarding the specific location, the database presents these two documents under the Albert Brauer Psychological Warfare Propaganda Leaflets Collection. They were both dated between 1950-1959, which was the rough span of when the war started.

Leaflet 1:

Leaflet 2:

Poetic Context:

The two poems are written roughly in the traditional 시조 “sijo” poem, which has traditionally three lines. It often explores metaphysical, romantic, or pastoral themes with order and form because each line has its purpose to extend the theme further until the last line where there’s a twist. There’s a counter-theme that swivels the poem in a different direction. Sijo, since the beginning of the Joseon Dynasty, was expected to be phrasal, lyrical, and witty. They were meant to be through music and songs, capturing the inner depths of the human soul and the complexity of nature and the world. In my own experience, they capture Korean culture, rooting in order and form, yet lyricism and music. It was a poem of wit and irony, yet powerfully romantic. What better way is there to express the “Korean-ness?”

Poem 1:

수천 숮자를 처음본자, 보고 더 벌수있으려나?

피와 땀, 눈물갇고 이런 숮자를 볼수있다

저승사자는 목슴만 얻고 이 전쟁에 부자가 될 걱이다

“It’s the first time I see 6 figures. I wonder if we can sell more?

I know what they mean now. You have to put all of your blood, sweat, and tears to have this kind of digits.

But it is only the Reaper who profits. From this war, it is only the Reaper who becomes rich.”

This poem was based on the first document I chose, the anti-moral propaganda against the North Korean Battalion. Maybe it was exaggerating, but it wasn’t lying. Lasting for 4 years until a stalemate, the war led to an estimated 2-3 million casualties for civilians alone. North Korea suffered 1,550,000 total casualties, both civilians and soldiers alike.

The poem was a mixture of twisting an idea of war and economics, casualties, and the presence of death. The Cold War, in its basic nature, could be seen through the ideological conflict between communism against capitalism. And the idea struck me of how economy and war play together to create something messy. By the words from the propaganda (casualties and death), I tried to recreate a poem that can capture the language and connotation of money and business. Figures. Money. Blood, sweat, and tears (Which mean more than one thing). Who actually wins in a war? And this is something I try to ‘twist’ at the very last line of the poem, where it is the reaper who collects the souls as the only one who can ‘profit’. In a sense, the original intention of the propaganda is lost because this isn’t just referring to a specific battalion, but everyone. There are no winners. Even writing through this poem, what’s left standing alone is the reaper.

Poem 2:

밤에 외로운 내집, 오늘도 내 남편은 충실하지 않다

아침에 쓸쓸한 우리 농토, 오늘도 내 아들이 부모를 도울수 없다

도당들아, 원리가 평와보다 더 중요하냐? 인구가 가족보다 더 중요하나?

“Tonight, I am lonely in my own home. Even today, my husband cannot be loyal besides me.

It’s morning, and the farmland is still cold and empty. Even today, my son cannot support or help his mother.

You communist puppets and vipers. Do you so value ideology over peace? Do you value a population over a family?”

The second poem was based on the other document I chose, the anti-communist propaganda against the Ill-Song’s regime. It struck me how the leaflet depicted protesting women who were demanding the regime to bring back their families that were either taken away or killed from the war. There was a connection this document made that was interesting to me more than just ‘communist = baddies’. It was about suffering and broken families, a foundational institute that’s a priority in Korea (and eastern culture in general). The war had superpowers- China and the United States- fighting for territory. But the war also had locals fighting for their country, their family, and a promise of safety. The history of Korea has been about perseverance. Persevering a cultural identity despite invasion from Mongolia, China, and Imperial Japan. It was about surviving through unity and community. So, what did it mean to face a regime that broke it apart?

The remix poem illustrates what I perceived as ‘familial problems’ often depicted through literature. Unfaithful husbands and disobedient children. But the twist wasn’t that they’re doing something wrong, but that they fail to do something right (to be a family) because of the regime. I think what’s maintained through the poem is this humanity that wouldn’t be there when you only see the war as an ideological fight between the superpowers. As an informational text, you’re supposed to memorize because of a test. Real people suffered from ideas on paper. It’s trying to reveal the consequences of abstract ideas in the real world. What we see in war are countries and armies, but for the poem, we experience families and individuals. The poem loses sight of the objective clarity on how the war affects the Korean civilizations. But at the very least, it’s a reiteration of experiences felt through the country and to the families that did their best to survive.

Bonus Poems

Poem 3:

보아라, 누가 인간들이 에덴 동산을 스스로 만들거라고 알았냐?

들어라, 누가 이 산과 강을 이동할 수 있었다고 믿었냐?

기역하라, 인생 끝에 다 저승사자 만난다. 인생에 절망은 그의 장난감이다

우리는 흙이니 흙으로 돌아갈 것이니라

“See, who would have known how humanity can create their own garden of Eden?

Listen, who would have known how humanity can move the mountains and the river?

Remember, in the end, we all face death. This road of hope and despair is just a toy.

For dust we are made, dust we shall return.”

Poem 4:

Athena: Are you listening? To this confession for you?

저승: 사랑에 빠질대 보다 나오는게 흴씬 어렵군

저승: 너는 지혜와 전쟁에 여시이다. 그래서 묻고싶다, 둘이 같이있느냐?

Athena: Do you think the same as me? If you’re not sure, then stay with me and then, we can be together.

저승: 우리는 같이 울고, 같이 진다. 희망. 절망. 우리는 같은 장마에 같고있다.

Athena: We weep together and lose together. Hope. Despair. We share the one rose together.

The additional two poems I’ve added were produced out of the inspiration of the Korean war. It was a war of participation. The United States. China. Turkey. The Netherlands. We were taught who our allies were at the time. We remembered that this world was never in isolation and that there will always be consequences from the influence we have on one another. One of the noticeable consequences is the rapid expansion of Christianity in Korea, a new force of spirituality and institutional presence that would forever change Korean culture. Through the church (both catholic and protestant), there were new universities and institutions, and hospitals. Yonsei University, which started as a theology school, became Korea’s #2 university… I mention this because my mother works there as a professor. There was a new outlook to understand the world. The poem itself depicts the way to see the war. The Korean War introduced a new scale of bombing tactics and air raids- something to decimate an entire landscape. It showed more air raids than any other war we had seen- even surpassing World War 2 and Vietnam. Dust and soil would rip through the air. Mountains and rivers, landscapes that were bountiful in Korea, would be broken down. The war reminded everyone of the capability, yet atrocity humans are capable of.

The second bonus poem touches on the more romantic intent of the Sijo poem, depicting a dialogue between Athena and the Korean Grim reaper “저승사.” The poem is built on contrast: Athena being both the goddess of wisdom and war while Grim Reaper is the harvester of death. There is her symbol as the model of Western Civilization while he is Eastern. It was built on my own experience as well, jumping between Eastern traditions and values growing up, while obtaining more Western education through college. It’s a dance, an idea that both are connected, yet distinct from one another. This distinctive unity marked my experience writing the poems, as well as my experience in college as well.

Conclusion

The remix of the poem was an opportunity for me to reimagine the education of the Korean War through the experience of the locals. It was understanding the story of my grandparents and my country I was a part of for a large part of my life. It was a complicated time because it was about fighting against your own family and your own nation torn in half. Your allies were your foreigners. I think in the end, the poems are about fortitude, perseverance, and hope. The war continues to this day, and the split between the North and the South is a reminder that there is still trauma, damage, and animosity. The remixes may lose the original intention of the propaganda, but they kept the rage against injustice, senseless violence, and brokenness of how the Koreans felt at the time. And what’s founding underneath all that is the hope that the Korean identity still lives on. And that one day, it can mend itself back together and be whole again.

Sources:

http://www.digitalhorizonsonline.org/digital/collection/ndsu-korea/id/81

http://www.digitalhorizonsonline.org/digital/collection/ndsu-korea/id/502/rec/7