Introduction

For as long as I can remember, my nose was always stuck in a book. I loved reading, and my love for reading and books only grew exponentially as time passed. My favorite genre to read was Young Adult Literature, as that genre encompassed many things; so when the idea of this project was introduced to me, I knew I had to focus on 21st Century Young Adult Literature. Having recently taken an Intro to Rhetoric class, I was introduced to the concept of identity, a topic that appears in Young Adult Literature because at that time—that is, when you’re a teenager—that you start finding yourself.

And suddenly, my project sprang to life.

As the books I read increased, so did my observations of how protagonists—both male and female—of these stories find and realize the concept of identity. I remember specifically reading books with female protagonists—works such as Twilight and Divergent—and recognizing the pattern that in order for them to realize who they are, they must sacrifice. Sacrifice family, friends, even parts of who they are themselves in in order to have self-identity, while books with male protagonists realized who they are internally; and used adventure/quests to help find who they are.

This was the foundation for my project: Examining the difference in how female and male protagonists acquire/discover the concept of self-identity as well as “what factors contribute to the process of identity?” I would later learn that these would also be my research questions.

From there, my project starting snowballing, I suddenly had a lot more insight to my project and how I would work on it and develop it. The first thing was my corpora. I needed two corpora because I was comparing male and female protagonists, so I went to work remembering Young Adult Literature I loved reading that was from the 21st Century. A lot of the books were easy to find; I didn’t really have to look any farther than my interests. I gathered all the books that perked my interested in my teen years, as well as doing some Googling to find more books for my female protagonists that were geared for younger audience because my male protagonist corpus had quite a few books that was targeted towards readers on the younger side of teens, and I wanted a balanced corpora.

My final corpora of works looked like this:

Male Protagonists

- The Lightning Thief by Rick Riordan

- Everyday by David Leviathan

- The Kite Runner by Khaled Hosseni

- Looking for Alaska by John Green

- The Maze Runner by James Dashner

- Hatchet by Gary Paulsen

- Holes by Louis Sachar

- Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone by J.K Rowling

- Simon vs. the Homo Sapiens Agenda by Becky Albertalli

- An Abundance of Katherines by John Green

- The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie

- The Perks of Being a Wallflower by Stephen Chbosky

- I Am Number Four by Pittacus Lore

- 13 Reasons Why by Jay Asher

- Paper Towns by John Green

Female Protagonists

- The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins

- Twilight by Stephenie Meyers

- Divergent by Veronica Roth

- Hush Hush by Becca Fitzpatrick

- City of Bones by Cassandra Clare

- Shatter Me by Tahereh Mafi

- The Fault in Our Stars by John Green

- If I Stay by Gayle Forman

- Speak by Laurie Halse Anderson

- Stargirl by Jerry Spinelli

- The Lovely Bones by Alice Sebold

- Maximum Ride by James Patterson

- The Book Thief by Markus Zusak

- To All the Boys I’ve Loved Before by Jenny Han

Once I made my corpora, I erased everything not relevant to my project, things like page numbers, acknowledgements, etc. My choice also entailed that I deleted titles of chapters, which were often creative and gave insight to the contextualization of the novel; however, for my purposes, they didn’t contribute anything to my project, so I chose to remove them.

Scholarly Article: Gender and Agency in Young Adult Fiction by Weissman and Swanstrom

As I was pondering the relationships between Young Adult literature and identity, I actually stumbled across a scholarly article, titled Gender and Agency in Young Adult Fiction by Jodi Weissman and Elizabeth Swanstrom that really hit the nail on the head in terms of what I was interested in examining. The article was about gender and agency in Young Adult Fiction, and even featured one of the same novels that I had in my own corpus, Twilight. The article examines the emotional discourse relationships between desire-happiness and conflict-peace between genders, which is something similar to what I focused on in my query of ‘fight’.

This document was extremely invaluable to me through this whole process because although it focused on close readings within the novels, it recognized patterns between protagonists regarding their sex and their identity. Having this as a reference to go back to was crucial to me, as I wanted to expand on their findings, and then I also wanted to take it a step further by examining my own research questions within their guidelines.

The Research

Gendered Character Descriptions

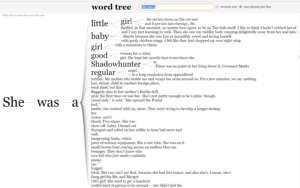

Moving from the theoretical framework to the actual research was quite exciting. The first thing I did after compiling both corpora was using the Word Tree Tool to see what relationships existed within and between the different gendered corpora. Below are the two results I got when I searched within the female protagonist texts.

As you can see, the difference is pretty obvious.

Women are categorized by words like “little,” “little girl,” “bitch,” ‘goody two-shoes,” and “show-off.” The words used to describe men are drastically different: “gifted athlete,” “tall heavily muscled man,” “tribal elder,” “human.” The results for how “he” and “she” are described in male protagonist books are similar to those for the ones for female protagonists, which I was surprised at how much overlap these two corpora would have, in terms of describing their main character; I would’ve thought there would’ve been a greater distance in how male and female characters are described.

Gender and Identity

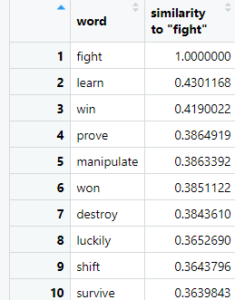

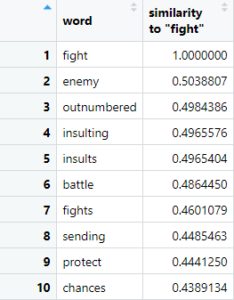

From there, I moved onto word2vec. One query I tested was the difference between female and male protagonists and how they differ in terms of the word fight. I first queried it with female protagonists and these results popped up for the words closest to ‘fight’:

Female Protagonist

Female Protagonist  Male Protagonist

Male Protagonist

The results show that for female protagonists and the word ‘fight,’ the proceedings and outcomes are of more depth than male protagonists. In simple terms, when the word ‘fight,’ appears in the female protagonist corpus, there’s an underlying moral as to why. Take, for example, result number 4 from female protagonists: prove. Female protagonists in Young Adult Literature often times have to prove themselves to be ‘worthy,’ ‘strong,’ ‘independent,’ etc. Whereas the results for male protagonists are shallow and don’t have a lot of interpretation open to them, it’s mostly about the battle itself, and not the implications of it. This relates to my overarching question of identity because through fighting—whether it be a physical or psychological fight—it shapes not only how the readers and other characters viewed the female protagonist, but also how she comes to view herself. The idea that a fight is employed in order to prove some aspect of the female protagonist, while a fight for male protagonists is simply another run-of-the-mill activity that they engage in is very much aligned with what I expected.

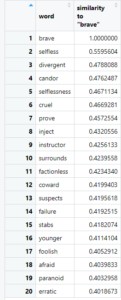

Another query I found particularly insightful was when I looked at the words closest to ‘brave’ in my male protagonists corpus, and one of the top words that popped up was a slur used against gay men. I thought this was important to mention because though it pertains to one specific text in my corpus, Simon vs. The Homo Sapien Agenda, I thought it was interesting that the slur was associated with being brave, which directly ties into my research questions of identity and what factors contribute to these concepts. The idea that being called a slur, translates to the protagonist being brave is fascinating because it implies that, ‘bravery’ and ‘conflict’ are some factors that contribute to male protagonists realizing their identity.

Male Protagonist (slur blurred out)

Male Protagonist (slur blurred out)  Female Protagonist

Female Protagonist

Similar to the male protagonists, a lot of the results pertained to one book—Divergent by Veronica Roth—for the female protagonists. However, these results are very telling as well! A lot of the words closest to brave are ‘coward,’ ‘failure,’ ‘foolish,’ ‘afraid,’ and ‘prove.’ Again, this is interesting to me because if you remember, the word ‘prove’ appears in the ‘fight’ results from earlier! This query supports the idea that in 21st Century Young Adult Literature, female protagonists have to constantly prove something to someone else; prove that they’re brave, prove they can fight, prove themselves worthy, and by proving this to either others or themselves, they then adopt the characteristic ‘brave’ for themselves, therefore shaping their identity.

The last point I want to touch on here, is the fact that the both words selfless and selflessness appear—which is a pattern we see a lot with female protagonists—in terms of realizing their identity. Additionally, this is something I noticed when I would read these beloved novels, and even Jodi Weissman and Elizabeth Swanstrom refer to this in their paper: “However, a trend in contemporary young adult fantasy seems to shift the motivation behind adolescent female identity search from self-realization to self-sacrifice.” (Weissman and Swanstrom, 6).

Takeaways

A lot of the results that I found were consistent with the Weissman and Swanstrom article and what I hypothesized, in regards that self-sacrifice and self-identity are tied together very heavily for female protagonists while that is not the case for male protagonists. These queries brought to light a lot dominant themes—for both male and female protagonists—that are situated in Young Adult Literature. The main theme is that in the search for identity, female protagonists often adapt self-sacrificing behaviors to reinforce and discover who they are, while male protagonists do not; and often have a more simple, and almost linear realization of identity.

Limitations and Future Research

One thing I will say about the challenges I had in using word2vec, in regards to my research question, was that my research questions predominantly look at relationships within the text, and this project wasn’t so much about textual analysis/close reading. However, my second research question about what factors contribute to identity are able to be examined with word2vec, as factors like “family,” and “sacrifice” are common in these coming-of-age books. Nevertheless, I was up for the challenge of having to dig a little deeper to explore my research questions, and using word2vec and wordtree produced some very satisfying and insightful results, so I’m glad I saw it through.

In terms of future research, I’d really like to expand on the research I did because I found the results fascinating—albeit a little hard to discover without doing a close reading of my corpora—and I couldn’t fit all my thoughts into this blog post without turning it into a dissertation. I also think future research could benefit from exploring the difference in how authors describe the opposite sex in their novels, as that was an idea that also peaked my interest.