Even as a descendant of the digital media age, I grew up between the pages of print. Teen Vogue and Seventeen were my introductions to journalism just as much as The New York Times. The difference to me, as a young journalism student but also a young woman, is that the Condé Nast publications balanced the complex scale of serious, investigative reporting with evergreen, female-focused content. I could read pieces about dismantling the patriarchy with a sidebar about the best colors to paint my nails. I didn’t have to chose between being feminine or being informed: I could be both.

Opposition

But this opinion isn’t a popular one. For many, women’s magazines represent the antithesis of women’s empowerment. Angela McRobbie, in detailing the feelings of the 1970s feminist movement, described their effect as “nothing but convinc[ing] readers of their own inadequacies while hooking them into the consumer culture that they could buy their way out of bodily dissatisfactions and low self-esteem.” It cannot be argued away that these magazines have stakeholder objectives, advertising goals, and profit margins to meet. When feminism meets capitalism, does its language about women change? In a time when print publications are on the decline, do they still cling to the patriarchal portrayal of women as in the past? And do any of these voices change when the audience is shifted to men? These were questions I was interested in investigating using vector space analysis as my medium. To make this analysis, I looked at over 50 issues of Vogue and GQ (formerly Gentlemen’s Quarterly) to try to discover any differences in the representation of women in magazines targeted at female or male audiences.

Analysis

Process

To answer the questions around the language and connotation of women, I used a series of word embedding models titled word2vec. They enabled me to map out the words from 27 issues of Vogue and 29 issues of GQ in vector space and rank their similarities based on context and usage. I used the two corpora to compare changes in tone or word choice for female (Vogue) or male (GQ) audiences. All issues were from 2015 and 2016 in order to draw results that would reflect their contemporary coverage. There is representation from all seasons throughout the year to account for changes in reporting topics such as the United States presidential election in November 2016 or fall fashion in September. All magazines issues were downloaded from Archive.org, a non-profit archive of books, websites, and videos. To properly format the .txt files for analysis, I removed the HTML tags that appeared at the beginning and end of each document. While reviewing the raw text, I made the decision to keep text even if it was not about the content of the articles. This included magazine advertisements. To properly analyze the language used to describe women’s issues, I believe the messaging in the advertising material is equally—if not more, due to McRobbie’s earlier claim about consumer culture—relevant.

Search Queries

Language around individual women

My initial queries were using the aptly named “closest to” model which returns a table of words with the highest similarity to any given word. To begin, I looked into the words most related to “woman.”

I noticed a higher frequency in words related to domesticity and traditional gender roles within GQ, such as “wife,” “mother,” “pregnant,” and “husband.” The list continues, primarily with nouns that describe a woman’s relationship with others in either a romantic or familial context. In comparison, the words returned from the Vogue corpus containing a higher frequency of adjectives to describe women with a mix of positive and negative connotations. These include “confident.” “young,” “awkward,” and even “badass.” There are no nouns that deal with relationships or dependencies, but rather qualities of oneself or others. While GQ uses “woman” as a way to view them in context with another person, Vogue uses the term to describe them as an individual, possibly debunking the myth that women’s magazines reinforce the idea that “women are defined by the children and men in their lives” (Demarest & Garner). Based on these queries, that claim is better suited for GQ.

Women in politics

Word2vec is also able to construct similarities between a sum of two or more words, so I was able to move beyond the single searches exhibited above. I was interested in dissecting the community of women discussed in these magazines and investigating if there was a change of connotation of words when divided by different fields or professions. Two large (and possibly clashing) areas of coverage for these magazines include politics and fashion. To study this job binary, I searched for the closest terms to “women” + “politician” and “women” + “model.”

Vogue’s results for “women” + “politician” skewed more negative in comparison to GQ, which I believe can be attributed to the lack of representation of women in politics. Their stories most likely focus more on the difficulties of the campaign process and stigmas to overcome in office. Terms such as “violence,” “dismal,” and “disappointment,” contribute to that claim. However, there were still small pieces of hope in this coverage. Words such as “outspoken,” “advocate,” and “courageous” appeared, contributing to a more positive picture of women in these positions. GQ had more of a mix of coverage, which words like “unafraid” and “despicable” appearing right next to one another.

Women in fashion

The results for “women” + “model” mostly included names of models featured in the magazine, which was fascinating to see how the computer could name these women based only on their occupation. It was also an easy way to compare models that are discussed or featured in both magazines, such as Gigi Hadid whose name appeared in both queries. GQ’s male audience was apparent in their results by the appearance of “male” and “girlfriend,” showing that the women in these modeling occupations are often the target of romantic interests for men.

Women in families

Because many of my results were describing women in the context of their relationship with others, I wanted to further investigate those connections. One of my initial research questions revolved around whether these texts are reinforcing patriarchal ideas, so I wanted to investigate the relationship between a woman and a child: two core characters in the patriarchy.

GQ’s results were very similar to the initial search for similarity of “woman,” with words like “mother,” “wife,” and “husband” appearing. Vogue’s results, however, returned much more emotive adjectives. Terms like “determined,” “terrified,” “upset,” and “bullied” led me to believe if perhaps their coverage focused more on young (another term that appeared quite high on the list) or single mothers raising their children alone. While GQ’s query returned a complete character list of the stereotypical American family, Vogue felt like it was tackling a more non-traditional narrative.

Beyond heterosexual relationships

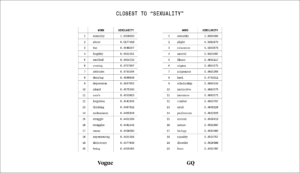

Most of my targeted questions and results thus far have been primarily heterocentric, focusing on romantic relationships being defined as a man and woman or families as being composed of a mother, father, and child. McRobbie’s research found similar trends—that “the whole cultural field of the magazines take heterosexual desire as constituting a framework of normality.” I decided to focus some of my final searches on the term “sexuality” to see how sex and sexual preference is discussed in these magazines.

Vogue’s results confirmed many of McRobbie’s ideas that “lesbianism remains, for younger readers, a social issue rather than a sexual desire.” The most similar words seemed to deal with the anxiety of coming out, with words like “terrified,” “denying,” “depression,” and “afraid.” All skew toward the negative experience of coming to terms with your sexuality rather than celebrating or even educating girl’s about their own. I was impressed with how high “education” appeared in GQ’s results, which led me to believe that for some men, this magazine is their primary form of sex ed. Although their discussion of women may be questionable based on earlier queries, any open discussion about sexuality is better than none.

Takeaways

The most interesting dichotomy to emerge from my research was the dichotomy of a woman being viewed as an individual or dependent. Vogue’s coverage heavily emphasized one’s personal emotions or feelings while GQ’s content seemed to skew toward women’s role in families and relationships. Reflecting on the mission of the respective publications, this representation makes sense. Vogue is meant to represent the interests of women, while GQ is the authority on men. This leads to women being the main characters in most stories published in Vogue, while in GQ they may play only a secondary role. This inherent power structure, however, leads to GQ perpetuating an image of patriarchy much more often than Vogue, as evident in several of the searches explored. And for the question of how feminist these magazines really are, McRobbie nicely words her answer to that question by asking in return: “But ‘we’ feminists are many and diverse, and who is to say who the real feminist is? And is it any wonder then that younger generations of women and their magazines join forces in rebelling against us too, as well as the moral guardians who condemn their reading material?”

In the future, I’d love to explore the more nuanced way the magazines’ coverage is influenced by their publishers’ investments or business partners using tools that can create maps of possible textual relationships. For now, I’ll continue to consume the critical takes of Donald Trump alongside top ten fashion trends: a unique binary that only Vogue can provide.

Works Cited

Demarest, Jack and Jeanette Garner. “The representation of women’s roles in women’s magazines over the past 30 years.” Journal of Psychology, vol. 126, no. 4, Jul. 1992, pp. 347-368.

McRobbie, Angela. “Back To Reality?: Social Experience and Cultural Studies.” New York: Manchester University Press, 1997. Print.