Introduction

In this post, I’ll be using word vectors to explain what I believe to be the cause of the significant lack of women in the world of engineering.

While I’m certainly no expert authority in the world of STEM or that of feminism, I do find myself taking quite an interest into why these fields

are so often devoid of female members. And while I’m aware that this absence of a female presence is the result of countless factors over the course of years

and years, I thought it might be interesting to try and make use of word vector analysis to get at the origin of these factors in the mid twentieth century. So,

with my perspective in mind, allow me to try to answer the question, “Why are so few women interested in a career in engineering, and what factors from the

previous century have contributed to this sentiment”.

Source Material

The first step in this endeavor was to determine what my source material would be. For word vector analysis to hold any really weight, the source upon

which it is being applied should be compromised of minimally a million words. So, with this prerequisite in mind, I decided to create a corpus of three texts: a scientific

journal from 1930, 1942, and 1960. These three journals were all published by the Engineering Institute of Canada. They, to oversimplify their contents, summarize

discoveries and successes in the engineering world for the given year. Thus, my thought when selecting my sources was that by analyzing these entries, I could potentially use

word vector analysis to determine how the accomplishments of women and the accomplishments of men were received: positively or negatively. So, once I determined

that these sources would aid me in my questioning, I had to, for lack of a more profound phrase, clean out the garbage. These documents were in many ways mechanical,

containing thousands of lines that were simply metadata. Publication information, committee members, dates, costs, etc. Nothing that helped me to get any closer to answering my

question. So, in order to strip most of that away, I made use of regular expressions. Essentially, they enabled me to mass remove parts of the text that I didn’t deem relevant. See

below for a list of the expressions.

-

- ^([A-Z\s]+)$ : Used to remove lines with only capital letters<\li>

- ^.{0,4((\r?\n)|$) : Used to remove lines of length five or less<\li>

- ^[A-Z][.].* L Used to remove lines that start with a capital letter followed by a period<\li>

- ^[t•][A-Z][.].* : Modified expression from above

These expressions are simply placed into a typical find/replace function that one might find in a word processor or a browser. These expressions handled most of the metadata,

but I still had to comb through the data manually (which was quite cumbersome). Had I more experience with regular expressions, I most certainly could’ve parsed through the document a bit faster,

but it was more practical to manually remove elements. Once the three documents were properly cleaned, I combined them into a single text document, thus creating a file fit for some word

vector analysis.

Analysis

Single – Term

The main basis for this undertaking is word2vec, a tool created by Ben Schmidt, Assistant Professor of History at Northeastern University. While I’ll give a brief summary of how the tool functions,

I’ll link Professor Schmidt’s article that describes his tool here. Essentially, this tool allows for a large corpus to, when properly prepared, represent words as vectors. Allow me to provide a visualization:

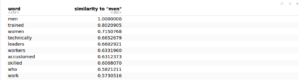

This chart displays the first ten words that are most similar to the word “men”. In other words, these given words appear next to “men” the most in the corpus. This is a very simple example of word2vec,

and really details the bare minimum of what this tool is capable of. The rest of the examples I give will either contain more than one term or will detail an analogy. So, after searching for the top ten words most

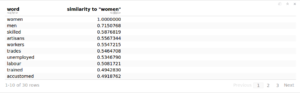

similar to “men”, I wanted to find out the top ten words most similar to “women”.

For the most part, the results were similar. Words like trained, artisan, and skilled came up. But, there were two notable differences: the absence of the word “leader”, and the presence of the word “unemployed”. It would seem to me that this difference would denote that men were considered leaders of the field of engineering during this time period. The word “unemployed” is rather interesting here, and while I feel that the lack of the word “leader” is more substantial, it’s worth noting that more negative terms are associated with women than men.

Multi – Term

Another use for the word2vec tool is searching for terms closest to two words. I’ll spare you a pile of rather unnecessary visuals, but allow me to break down my findings. When searching for “men” + “success”, some of the top results included “leaders”, “forefront” “marvellous”, and “cultivate”. A collection of quite positive terms, or at least I should think so. I can’t remember that last time anyone referred to myself or my work as quote “marvellous” (Canadian/British spelling). Then, I ran a search for “women” + “success” , and what I found was interesting. Many of the same terms appeared, including “leaders” and “forefront”, along with some others such as “skilled” and “successful”. But, the term “heart” also appeared fairly high in the list. Curious, that a term that typically denotes empathy and care is used in regard to men but not women. Suggesting, I should think, that women are most emotional than men, at least in this case. To me, this represents one of the many stereotypes that impact women not only in STEM, but in the workforce in general. That women are more emotional than men and thus less useful. This stereotype without a doubt impacts the careers of women today, and even in this very technical piece of text, a summation of engineering reports, the stereotype of women as emotional peeks its head out.

Analogies

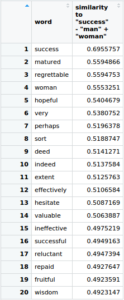

My final use for word2vec that I found quite interesting is the ability to search for analogies. Bird is to air as fish is to water. Men is to success as women is to “…”. So, here are the first twenty terms produced for searching for the previous analogy.

Note some of the terms here: regrettable, hopeful, hesitate, ineffective, reluctant. Certainly not words that would inspire confidence in any kind of discovery or research. Even the word perhaps adds to this general sense of uncertainty. Uncertainty that, I would assume given the context, that is made in reference to a finding by a woman.

Take-away

What I found in my research is that even in the most technical of texts, women’s works and contributions to the engineering world were met with distaste and hesitation. So many of the results from the analogy search add to this unmistakable air of uncertainty. That just because a woman published this work, it was somehow, less credible. I certainly would not want to launch a career into a field that historically disregards the work of women purely because of their gender. Part of the inspiration for me to investigate this issue is derived from a text published by the American Association for University Women, titled “Why so Few?”, which discusses the absence of women in STEM fields as undergraduates and explains some of the reasons why this is the case. An entire section of this text is dubbed “Stereotypes”, and to quote the section:

“A large body of experimental research has found that negative stereotypes affect women’s and girls’ performance and aspirations in math and science through a phenomenon called “stereotype threat.” Even female students who strongly identify with math—who think that they are good at math and being good in math is important to them—are susceptible to its effects” (Hill, Catherine)

These stereotypes definitely exist in the scientific journals I analyzed. Every word2vec search supports the existence of both stereotypes discussed in the section: “girls are not as good as boys in math, and scientific work is better suited to boys and men” (Hill, Catherine). This statement is supported by the single term search alone. “Men” yielded the term “leader” while “women” simply didn’t. I don’t think this analysis could be better boiled down to a single result. Women today are less likely to build careers in STEM fields because of the negative stereotypes that have been developed and reinforced over countless decades.

Works Cited:

“Engineering Journal 1930 : Engineering Institute of Canada : Free Download & Streaming.” Internet Archive, Montreal, Engineering Institute of Canada, 1 Jan. 1970, archive.org/details/engineeringjourn23engi.

“Engineering Journal 1942 : Engineering Institute of Canada : Free Download & Streaming.” Internet Archive, Montreal, Engineering Institute of Canada, 1 Jan. 1970, archive.org/details/engineeringjourn25engi.

“Engineering Journal 1960 : Engineering Institute of Canada : Free Download & Streaming.” Internet Archive, Https://Archive.org/Details/engineeringjourn43engi, 1 Jan. 1960, archive.org/details/engineeringjourn43engi.

Hill, Catherine|Corbett Christianne|St. Rose Andresse. “Why So Few? Women in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics.” American Association of University Women, American Association of University Women. 1111 Sixteenth Street NW, Washington, DC 20036. Tel: 800-326-2289; Tel: 202-728-7602; Fax: 202-463-7169; e-Mail: Foundation@Aauw.org; Web Site: Http://Www.aauw.org, 30 Nov. 2009, eric.ed.gov/?id=ED509653.