An Introduction to the Harry Potter Fandom

Harry Potter is considered by many a turning point in literature. For the first time in recent history, a book written for children and teens was a worldwide sensation. When the final book hit shelves, it sold 11 million copies in the first day. The movies made over 7 billion dollars. The brand is now valued at over 15 billion dollars. It has become a part of the cultural zeitgeist with celebrities being asked their Hogwarts houses. The fans are studied in an academic setting. It has also had a long-term effect on how we are fans of books. In previous eras, the love of a book stopped at book signings and fan clubs. Harry Potter changed this. It was one of the first books to have a fanbase raised alongside the internet. This made it easier for people to connect over long distances. This also led to an extensive fanfiction collection. There are over a million works of Harry Potter fanfiction on the internet ranging from the short single scene “one-shots” written by 10-year-olds to works far longer than the books themselves written by established authors and later edited into important books. The most interesting quality of this archive is the fact that writers of this fanfiction took a fiction criticized in the modern era for its lack of diversity and created their own diversity. From the rise of Black Hermione to the infamy of “slash” ( writing about homosexual pairings that do not appear in the original text), these alternative identities are now so popular that the amount of relevant fan material parallels that of the original text. For example, there is far more material about the romantic relationship between Harry Potter and Draco Malfoy than there is for the original pairing of Harry Potter and Ginny Weasley. Not only are these beliefs held, but they are defended by fans using the original text as evidence. For example, Harry’s obliviousness about romantic relationships is often used to argue that any number of relationships could have been happening in the background and Harry would have been none the wiser. in the article Harry Potter and the Fan Fiction Phenom, it is stated,

“When asked what attracted them to the [Harry Potter] universe, in particular, the respondents repeatedly pointed out that there are considerable gaps in [J. K. Rowling]’s story. The novels are told from Harry’s perspective, and he often has only the most tenuous understanding of his surroundings. This leaves a lot of leeway for fan writers.”

In addition, fans of the Harry/Draco pairings are quick to point to the intense emotional turmoil between the two and point to other opposites attract romances like the titular pair in Romeo and Juliet and even Darcy and Elizabeth Bennett in Pride and Prejudice. Whether they are right or wrong, the arguments are often well-thought-out and articulate. Many scholars argue that the reason that these fan theories develop is due not to the text, but instead to the writers. These writers use fandom’s spaces to explore their own identities and emotions. This is perhaps best seen when looking at queer identities in the Harry Potter fandom. The article “Homosexuality at the Online Hogwarts” explores this,

“Fandom, especially Harry Potter fandom, offers young people the opportunity not simply to passively absorb queer-positive (and adult-approved) messages, but to actively engage with a supportive artistic community as readers, writers, and critics. Moreover, the identity-bending, pseudonymous nature of online fannish discourse affords fans a certain measure of concealment, which proves especially valuable for young fans who fear the consequences of expressing non-heteronormative desires.” (Tosenberger)

So, when the children who were first read Harry Potter as a bedtime story start to explore issues like sexual and romantic orientation, gender identity, race and ethnicity, and complex family situations, they turn to the familiar characters of the Harry Potter series to use as guides in their exploration.

How to Prove a Fan Theory

Even though fanfiction is sometimes a projection, that doesn’t make it less probable. A good character is always one in which a reader can see themselves. The malleability of characters is what makes fiction unique from other works of literature. So, when Rowling wrote characters that are blank enough for readers to enjoy themselves, she also created a universe ambiguous enough that most fanfictions’ theories would be right. So then, how do you prove a fan theory right? That’s what this project aims to explore. I hypothesize that if a fan theory paints a character in the same light as the original text in the commonly accepted literature, then that theory is feasible. For example, say you want to prove that Dobby the House Elf is a space alien. If you can take a large sample of “Dobby is a space alien” literature and, when compared to the original text, the two Dobbys share many of the same actions, descriptions, and core character traits, then Dobby could conceivably be a space alien. This test might seem outlandish but think about other continuations of stories. For example, in movie sequels, characters can have different clothing, can experience character growth, and even be played by a different actor, and, as long as the core of the character is the same, the sequel’s place in the universe is rarely argued. Quality can still be argued, but the legitimacy of a continuation is a lower standard than many think. The two challenges in this method are finding an accurate means of comparison and paring down to only core characteristics. For example, in determining core characteristics, one might argue that Harry Potter’s bravery is one of the core character traits. While this is very true throughout the books, we have no real means of determining if this is true outside an adventure/save-the-world mission. Maybe Harry Potter is actually very nervous and anxious in a romantic or social setting. This is a huge challenge also because every individual has their very own definition of what are the important character traits. The challenge of finding a means of comparison is in finding something that can represent character traits in a numerical setting. This is of course, impossible. The closest thing is finding a combination of established numerical methods that explore some aspects of the character. For example, while we cannot measure how beautiful someone is between two texts, looking at how others describe them in both texts with statistics representing compliments of physical appearance against the overall number of compliments, could be useful in helping to further understand this character’s experience.

Methodology

So, after explaining the complexity and challenges of this problem, how exactly did a computer prove that Drarry is possible?

To begin with, we collected a sample of fanfiction that was all tagged with one of the following tags related to LGBTQ identity. These are all tags which are commonly used within the Harry Potter fandom and all of them provided enough material to analyze.

- Asexual

- Bisexual

- Coming Out

- Gay

- Lesbian

- LGBTQ Character

- Nonbinary

- Pansexual

- Queer Character

- Queer Themes

- Sexuality Crisis

- Trans Character

Six relationship tags were also included including 4 same-sex relationships as well as a relationship between two characters often talked about in the context of a queer relationship. These relationships are the most popular pairings, in terms of quantity of fictions including their tag, for each Male/Male, Female/Female, and Male/Female. This also allows for a contribution to theories about all members of the LGBTQ relationships in the context of relationships.

- Draco Malfoy/Harry Potter

- James Potter/Lily Potter

- Luna Lovegood/Ginny Weasley

- Pansy Parkinson/Hermione Granger

- Sirius Black/Remus Lupin

- Ron Weasley/Hermoine Granger

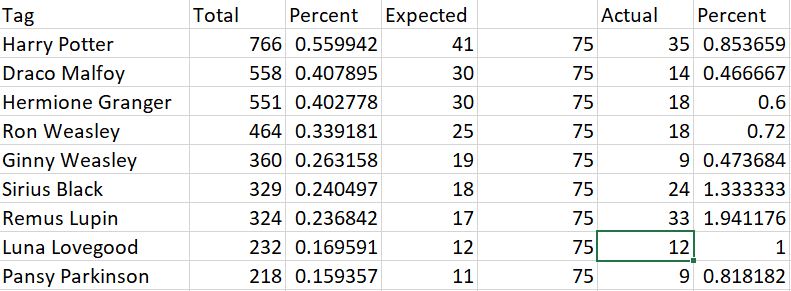

After the tags were selected, the amount of fanfiction had to be narrowed. Each of these tags had thousands of pieces of fanfiction about it ranging in size from a 1,000-word single scene to ones far outstripping the first and second Harry Potter books at 76,944 and 85,141 words respectively. Therefore, the project was limited to one site, Archive of Our Own. This website is known for having well-written fanfiction as well as being a place with a strongly established Harry Potter Community and an expansive archive with very little limitation on usage. Even within this single archive, there was a large amount of work to sort through to narrow the search and allow for the best comparability. Any fiction tagged as an “Alternate Universe” was eliminated as it could not fairly be compared to the original text. In addition, only completed works were included. Another layer of filtering was added when crossovers were eliminated. This means that any work tagged with multiple fandoms would be eliminated. For example, a story about Iron Man’s years at Hogwarts would not make the cut. In addition, the stories had to be in English, and they had to be tagged with the Harry Potter tag. This still left a fair amount of work, so a sample was taken. The top 30 fictions by positive reader reviews in the General, Teen, and Mature ratings were scraped. There were two scrapings completed, one of the tags, and one of the fiction itself. These were completed with a two-part Python-based scraper that was modified for this project. After the works were scraped into text files, the first part of the analysis began. The first task was using metadata to determine which characters should be analyzed. This was done by taking each tag and performing a frequency program to get a table of tags and the number of times they appear in that category’s text. This was then compared to the overall times a tag appeared. This allowed for the identification of a character being mentioned frequently in a specific context as opposed to simply being mentioned frequently overall. The picture below is an example of what this table looks like for the Trans tag.

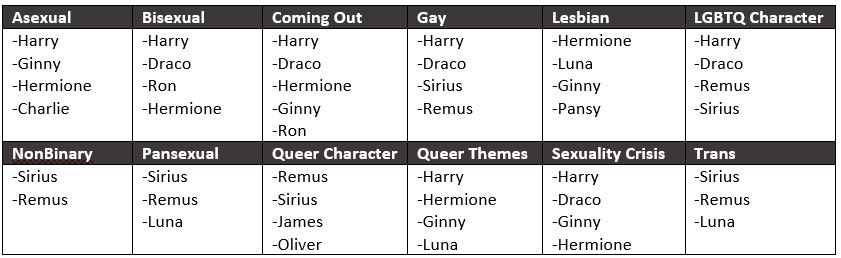

This was used to identify which characters should be specifically looked at for that identity. A base set of characters was looked at in every identity, but any characters that showed strong correlation to a single identity were examined in the context of that identity. The following graphic shows the characters selected for each identity.

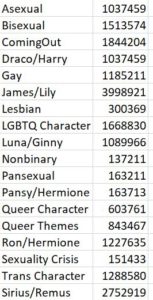

After the characters were identified, the models were run. A model was created for each of the tags containing all the text for fanfiction with that tag. The text word count for each tag is displayed below.

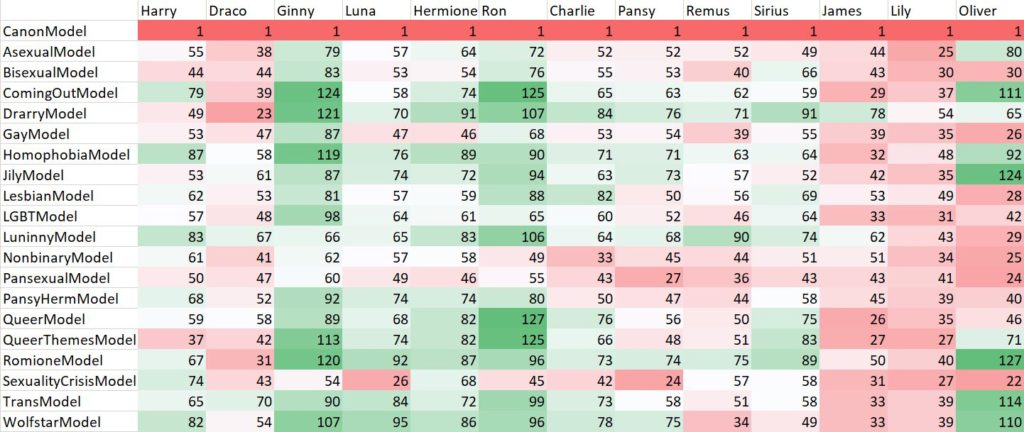

These models were then asked to generate the 500 words most closely related to the character’s first and last name (except for the Weasleys for whom the last name broadened the data too far). Then a natural language processing function was run to eliminate all extraneous unimportant “stop words”. These were then compared to the top 500 words related to that character in the original text. This then allowed for a number to be generated about the number of words that were the same between the two. After this analysis was completed, the following chart was completed. The green means a higher correlation while the red means a lower correlation.

The above charts have a couple of insights that are perfectly right…and some that are very wrong. I am going to focus on a couple of different points that reveal outliers or align perfectly with fan theory.

Results

The first outlier is in Draco and the Drarry tag. Obviously, Draco should have more similarity to the Drarry tag that at least a couple of other tags. This, therefore, presents our first challenge. This model will only work for narrative told in the third person. Many of these fanfictions are written in the first person meaning that the only mentions of the actual characters are in dialogue or mentions by the main character. Therefore, there is likely a lot of first-person narratives in the Drarry tag and therefore, there would not be a lot of mentions of his actual name and the mentions that do happen will likely not be related to the individual character.

The words that are an intersection with Draco are interesting.

- derisive

- draco

- drawling

- expression

- face

- favor

- fits

- granger

- hopelessly

- impassive

- longbottom

- malfoy

- malice

- manners

- me

- patrick

- potter

- quietly

- sneer

- sneering

- softly

- wipe

- zabini

These are really interesting because there is obviously enough third-person fanfiction to get some of Draco’s character traits. For example, sneering and speaking with malice are key traits of Draco in the book and it would make sense that these would be preserved in the fanfiction community.

The third-person vs. first-person problem is a good reason for many of the issues with the chart. For example, Harry has a big correlation with the Luna/Ginny (Luninny) tag. This is most likely because Harry is often portrayed as a friend to both Ginny and Luna meaning that in first person stories Luna or Ginny will spend time talking to Harry meaning his name will be mentioned in the same context every time. This can be confirmed by the fact that more than half of the words in the section are verbs or adverbs. Almost all of these words are related to addressing another person in conversation such as shouted, nodded, snarled, chuckled, or gasped.

One of the results that I find interesting that I agree with is the intersection between Luna Lovegood and The Sexuality Crisis. In much of the books, Luna is described as being above the drama and having a very fluid view of life in general. Therefore, I have always found it hard to imagine her having a sexuality crisis and this model tends to agree with me. Luna is not well correlated and all of the words in the intersection are more closely related to helping someone else through a sexuality crisis. This would match Luna’s core traits in the book of caring deeply for her friends and always being willing to help them regardless of personal cost.

Overall, this chart surprises in some places, while confirming in others. The challenge is figuring out how to make it more accurate. If given more time, I would have done some further customization of the word2vec model. For example, being able to write a program that would determine who is being referenced when a general pronoun is used and replacing the pronoun with their name. This would allow for the existing model to be far more accurate. The challenge of this is that it requires an understanding of grammar and English syntax that is challenging to machines. There are some advances in machine learning and natural language processing that would allow them to happen, but I did not have enough knowledge about how to build one specifically for this project. If continuing this project, I would probably start there. I think that would improve the accuracy of this model without great change to the actual model.

Also, another interesting area of research would be looking at how characters talk about themselves vs. how they are talked about. In this project, there was a great deal of time and energy devoted to dealing with comments about people, being able to distinguish between the two types of connection would also provide an interesting look into the autonomy and agency of queer identities, and of characters in general within the text. This would require an algorithm that could not only perform accurate pronoun replacement but could tell what was being said by the character to themselves, and what was being said about them, and even what was being said to them. All three of these provide an interesting look into how characters react and interact in fanfiction versus in published texts.

All in all, this project was successful in some regards. For example, in some cases, it did establish a means of proving a connection between a character and an identity. It was inconsistent and therefore non-repeatable. If also was only a small sampling of fanfiction. This contributed to strange results in some of the areas because 500 words was a small sampling of a a 100,000 word corpus. While this does provide more significance to the findings, it also leaves a vulnerability to fictions not accepted by the whole of the community. For example, a collection of all non-binary fiction could lead to fictions that are far out of character. Which while perfectly acceptable, would mess with the model and skew results.

- “Pop Rhetoric: Harry Potter and the Burden of Diversity.” UWIRE Text, 2016.

- Duggan, Jennifer. “Revising Hegemonic Masculinity: Homosexuality, Masculinity, and Youth-Authored Harry Potter Fanfiction.” Bookbird: A Journal of International Children’s Literature 55, no. 2 (2017): 38-45.

- Tosenberger, Catherine. “Homosexuality at the Online Hogwarts: Harry Potter Slash Fanfiction.” Children’s Literature 36 (2008): 185-207.

- MacDonald, Marianne. “Harry Potter and the Fan Fiction Phenom.” Gay & Lesbian Review Worldwide 13, no. 1 (2006): 28-30.

- Hijazi, Skyler, and Flinn, Caryl. Bodily Spectacles, Queer Re-visions: The Narrative Lives of “Harry Potter” Slash Online, 2007, ProQuest Dissertations and Theses.

- Urolagin, Siddhaling, and Likitha Satish. “Improving the Quality of Text Summarization Using Pronoun Replacement Technique.” Recent Trends in Electronics, Information & Communication Technology (RTEICT), 2017 2nd IEEE International Conference on 2018 (2017): 1991-995.

by Emma Reed